Accidental deaths of soldiers often receive less attention than battlefield casualties. However, for these soldiers of the First Virginia Regiment, sworn to fight for the Union, their fates marked some of the earliest losses of the Civil War. Were it not for a handful of brief newspaper articles and a sparse pension file, their stories of service and sacrifice might have been lost to history.

By Jon-Erik Gilot

I’ve spent several years accumulating sources for a planned book on the ‘first invasion,’ or George B. McClellan’s push from the Ohio River into Virginia’s western interior from late May – early June 1861. In a campaign hallmarked by swift, tactical movement and little significant fighting, accounts of heroic battlefield deaths are almost nonexistent. And those are seemingly the type of deaths that are memorialized in granite or bronze, or that leap from the pages of the latest Civil War study.

You don’t often read about the guy who was crushed by a train, the one who fell overboard from a steamboat and drowned, or the young soldier who shot himself in the leg. But does their manner of death make their sacrifice any less meaningful than those lives lost on the battlefield?

Regiments often experienced their first losses before ever seeing a battlefield. Disease and accidents were often the first recorded deaths experienced by soldiers in the field. And while these events may not make for engrossing reading in today’s popular history, these deaths were meaningful moments for soldiers on their way to war, sobering men to the realities that soldiering was a dangerous vocation. Regimental histories are replete with stories of the gloom cast over the men after losing a comrade-in-arms to friendly fire, drowning, or an unfortunate fall.

These early deaths – often experienced in camp or before active campaigning – also allowed the men an early opportunity to grieve or reflect on their new reality. Care was taken to secure and bury the bodies with military honors, or see the remains shipped home to loved ones. Accounts of their passing were editorialized in newspapers and memorialized in resolutions passed in their memory. Where modern readers may see carelessness in the circumstances of their demise, these deaths instead profoundly impacted the affected comrades, families, and communities.

While several companies of the 1st Virginia Infantry (U.S.) experienced battle during their ninety-day term of service (which actually stretched to a full 100-days), the regiment remarkably lost no men to hostile fire. When the regiment returned to Wheeling at the expiration of their term of service in late August 1861, the Daily Intelligencer noted:

“It is gratifying to know that notwithstanding the hardships which this Regiment has undoubtedly, but uncomplainingly endured, and the eagerness with which they have desired to pursue the common foe, not a single man has been killed by the enemy. Only three or four were lost by accident or disease…”[1]

Indeed, the regiment lost two men killed by accident, and another two who died of disease. Not memorialized on the regimental rolls are an additional two individuals who died by accident, one only days before the regiment departed Wheeling for the seat of war, and the other on the day they returned. In this occasional series, we’ll unpack the accidental deaths, and how their losses impacted both the regiment and community…

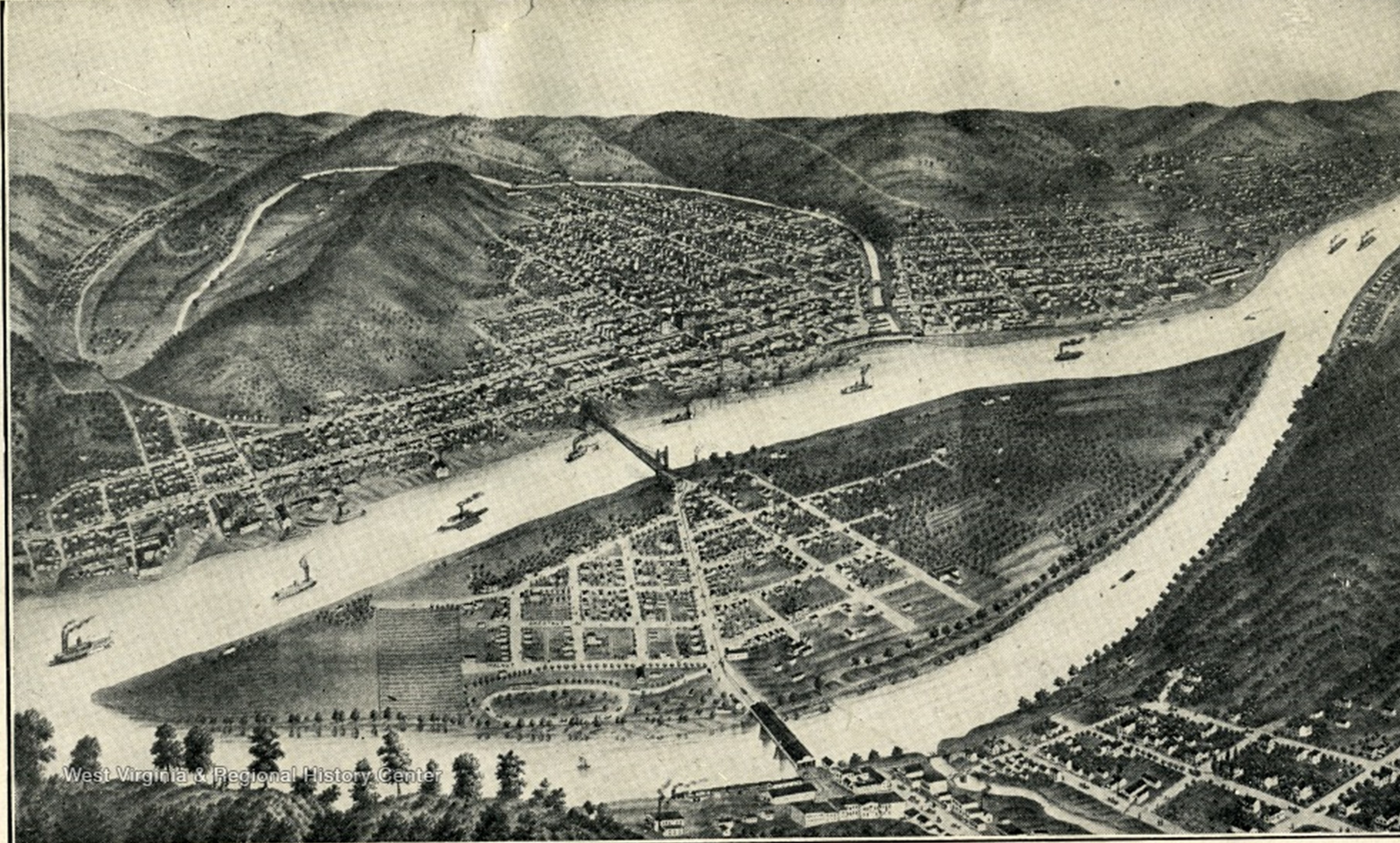

The first death of what has become styled as the ‘first campaign’ occurred before McClellan’s troops stepped off from the Ohio River. On Wheeling Island, in Virginia’s northern panhandle, a training camp was established in early May 1861, to accommodate companies arriving from neighboring counties in Virginia, Ohio, and Pennsylvania, for federal service.

Named Camp Carlile, in honor of senator John S. Carlile, the camp was situated on the fairgrounds of the Western Virginia Agricultural Society. The manicured grounds offered buildings and stalls to house the recruits, and a half-mile track ideal for perfecting military maneuvers. The companies assembling at Camp Carlile were quickly consolidated to form the 1st Virginia Volunteer Infantry, more commonly known as the 1st West Virginia.

At New Cumberland, the seat of Hancock County, a volunteer company was organized in early May 1861 under the command of Capt. Bazil W. Chapman. Fashioning themselves “The Hancock Guards,” the company was described as “splendid looking men” who were “all sons of well-to-do farmers and are noted for their good behavior and sobriety.” Hancock County pledged to cover the cost to uniform and equip the company as they departed for the war.[2]

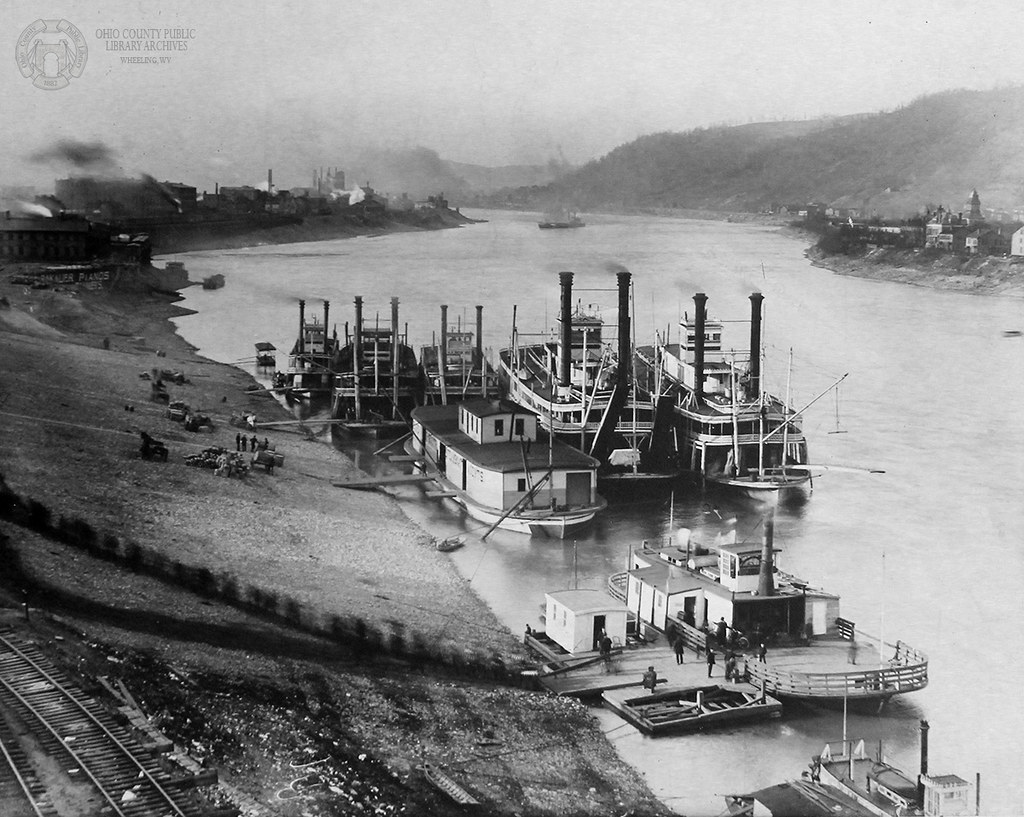

Reaching a full complement of 77 men, on May 19 the company chartered a steamboat to convey the men down the Ohio River from New Cumberland to Camp Carlile on Wheeling Island. The S.C. Baker, flagship steamboat of the S.C. Baker Agency of Wheeling, carried passengers and freight on a regular schedule between Wheeling and Pittsburgh. Described as having “a smiling and accommodating chamber maid, snow-white sheets and pillow cases, clean berths, a plentiful and luxuriant table, and…a gentlemanly clerk,” the Hancock Guard could not have imagined “a better floating home” for their trip to Wheeling.[3]

The S.C. Baker pushed away from the New Cumberland wharf on the evening of May 20, many of the Hancock Guards lounging and sleeping on the hurricane deck during the late-day voyage. At around 3AM on May 21, 1861, the steamboat swung into the wharf at Wheeling.

As the crew made arrangements to unload the men, another boat landed at the wharf, and in the darkness struck the S.C. Baker, startling the sleeping soldiers. Thomas J. Baker, a resident of New Manchester, Virginia, stumbled and fell from the hurricane deck into the water. His comrades watched in horror as Baker struggled and gasped before disappearing under the water. Baker’s captain later recalled that “all means…were made use of to save [him] but all to no purpose, he swam a short distance but drowned in a short time not exceeding ten minutes.” [4]

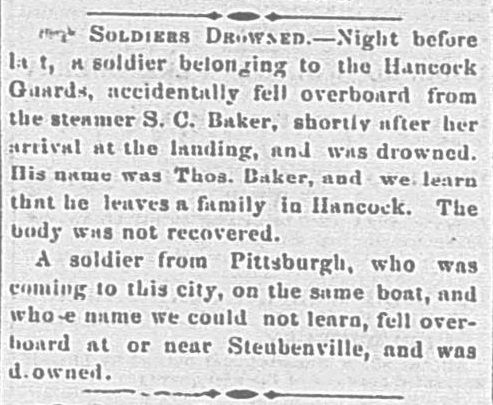

Baker had enlisted in the Hancock Guards only five days earlier and was recalled as “a sober, industrious man in his habits.” Several days later, a Pittsburgh paper published their own account of the drowning, writing that Baker…

“…had been up in town, and became intoxicated, and after coming on board lost his balance while on the guard of the boat and fell into the water. The watchman heard him fall in, but it being quite dark he was unable to render him any assistance.” [5]

Regardless of the circumstances, Thomas J. Baker left behind a wife and three young children. His death cast a pall over the Hancock Guards. The company took out an ad in the Daily Intelligencer offering a “liberal reward for the return of his body,” noting that the deceased may be recognized by his “dark complexion, dark hair and eyes; is about five feet nine inches high,” and at the time of his death was wearing “dark clothes, white shirt, black neck tie, and one thumb lost.”[6]

Later that same day, Baker’s company was mustered for federal service as Company I of the 1st West Virginia Volunteers. Four days later, Confederate troops burned two bridges on the mainline of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad near Mannington. In response, the 1st West Virginia was ordered south to repair the bridges, reopen the rail line, and prevent any further destruction in the area. On May 27, as the troops pushed south on the B&O, their train passed through Moundsville, Virginia, where later that day Thomas Baker’s body was found floating in the Ohio River. He had floated for seven days and more than ten miles.[7]

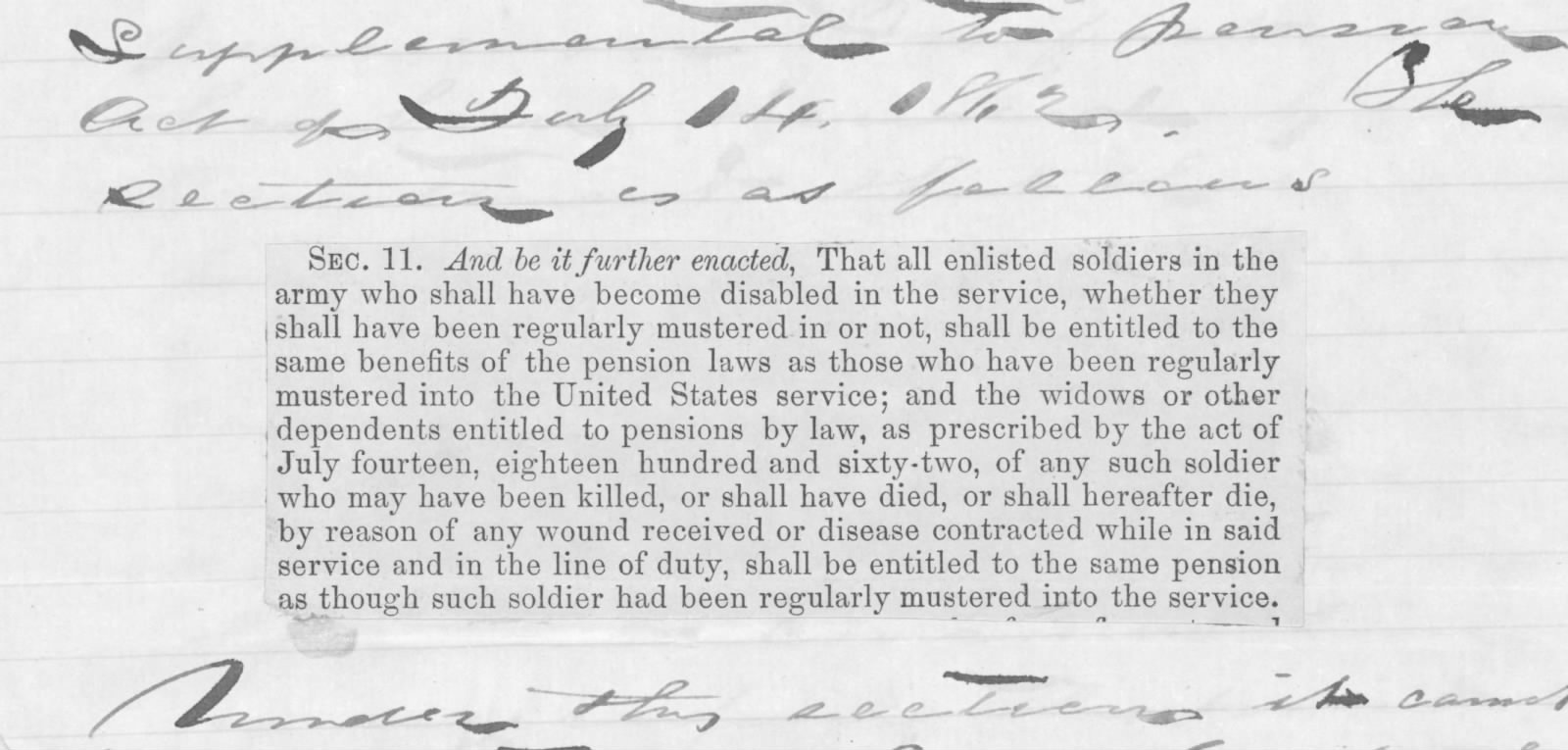

Hannah Baker, Thomas’s widow, did not initially qualify for a widow’s pension, her husband’s death coming one day before his company was mustered in for federal service. Her earliest claims for a widow’s pension as well as for her dependent children were rejected on the claim that her husband’s name was not carried on the regiment’s rolls. However, thanks to an 1864 amendment to the July 1862 Pension Act that allowed pensions for those soldiers who had enlisted but were not yet mustered prior to their death, Hannah was awarded $8.00 per month. She later remarried and died in 1879.

Baker was not the only casualty on the S.C. Baker‘s voyage to Wheeling . In the same article describing Baker’s death, the Daily Intelligencer notes that “a soldier from Pittsburgh, who was coming to this city on the same boat, and whose name we could not learn, fell overboard at or near Steubenville, and was drowned.”[8]

The Pittsburgh Post offers slightly more information on the earlier drowning, noting…

“A German, whose name is unknown, fell overboard from the same boat and on the same evening, and was drowned near Anderson’s Landing. It appears that he had joined one of the Pittsburgh companies at Wellsville and was on his way down to the camp at Wheeling. In attempting to step from the steamer to a barge which was in tow, he missed his footing and fell into the river and is supposed to have gone under the barge. He had been employed recently at the Columbia Coal Works, at Wellsville.”[9]

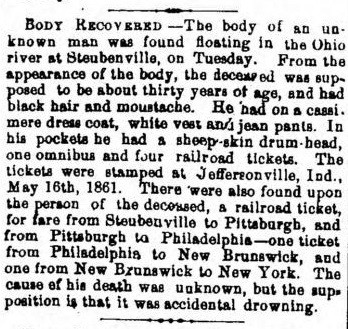

The German’s body was recovered on May 28, the Pittsburgh Post reporting…

“The body of an unknown man was found floating in the Ohio River at Steubenville, on Tuesday. From the appearance of the body, the deceased was supposed to be about thirty years of age, and had black hair and moustache. He had on a cashmere dress coat, white vest and jean pants. In his pockets he had a sheep-skin drumhead, one omnibus and four railroad tickets. The tickets were stamped at Jeffersonville, Ind., May 16, 1861. There were also found upon the person of the deceased, a railroad ticket, for fare from Steubenville to Pittsburgh, and from Pittsburgh to Philadelphia – one ticket from Philadelphia to New Brunswick, and one from New Brunswick to New York. The cause of his death was unknown, but the supposition is that it was accidental drowning.” [10]

Today, historians will not find Thomas J. Baker’s name in the 1st West Virginia’s regimental history. Even the location of his grave is not known with any certainty. His German counterpart remains unknown and almost certainly buried in an unmarked and forgotten grave. Their deaths represent perhaps the earliest wartime deaths of men enlisted or bound to enlist in support of the Union in a state that passed a secession referendum only days later. Were it not for a few brief newspaper articles and a slim pension file, the stories of their service and sacrifice would be lost to history.

[1] “A Great Demonstration,” Daily Intelligencer, August 22, 1861

[2] “The Island Camp,” Daily Intelligencer, May 22, 1861

[3] “The River,” Daily Intelligencer, May 28, 1860

[4] Hannah Baker Widow’s Pension Application, Fold3

[5] “Drowned,” Pittsburgh Post, May 23, 1861

[7] “Body Found,” Daily Intelligencer, May 28, 1861

[8] ibid, Daily Intelligencer, May 22, 1861

[9] ibid, Pittsburgh Post, May 23, 1861

[10] “Body Recovered,” Pittsburgh Post, May 31, 1861

Jon-Erik Gilot has worked in the field of public history for nearly 20 years. A contributing historian at Emerging Civil War since 2018, his research has been published in books, journals, and magazines. His first book for the Emerging Civil War Series, John Brown’s Raid, was published by Savas Beatie Publishing in 2023. Jon-Erik earned a History degree from Bethany College and a Master of Library & Information Science from Kent State University. Today, he serves as curator at the Captain Thomas Espy Grand Army of the Republic Post in Carnegie, Pennsylvania, and works as a corporate archivist and records manager in Wheeling, West Virginia.

2 thoughts on ““Only three or four lost by disease or accident…”: The First Deaths of the First Campaign”