One hundred sixty-five years ago, the Commonwealth of Virginia set itself on a course that would alter its history forever. The decision placed the state on the losing side of a devastating war that claimed hundreds of thousands of American lives, displaced families, split the commonwealth in two, and left farms, villages, and towns in ruin. Virginia’s foundational economic system was destroyed, the legacy of which historians continue to debate.

How did this happen?

Prior to 1860, no state had ever attempted to secede from the United States. There was no precedent and no clear blueprint for how such a step might be taken. The Constitution contained no provision allowing a state to withdraw from the Union, and many Americans regarded that Union as perpetual.

Others, however, maintained that each state had entered it in 1789 as a free and sovereign entity and therefore retained the right to sever the bond at will. As President James Buchanan summarized in his 1860 State of the Union address, secessionists believed “the Federal Government is a mere voluntary association of States, to be dissolved at pleasure by any one of the contracting parties.”

A large majority of Virginians believed secession was legally possible, even if many of them preferred to remain in the Union. That raised an unavoidable question: how would Virginia justify such a step? What process would formally signify the Commonwealth’s withdrawal from the Union?

Following Abraham Lincoln’s electoral victory, Governor John Letcher issued a proclamation on November 15, 1860, calling the General Assembly into special session on January 7, 1861, so that the representatives of the Commonwealth might “consider public affairs.” On December 20, South Carolina adopted an Ordinance of Secession.

When Virginia’s General Assembly convened in January, Letcher made clear his opposition to summoning a state convention. “I see no necessity for it at this time, nor do I now see any good practical result that can be accomplished by it,” he declared, though he conceded that future events might warrant such a step.

On January 12, the General Assembly passed a bill authorizing a State Convention. It cleared the House of Delegates unanimously and the Senate by a vote of 45 to 1. After the Senate added several amendments, the measure became law on January 14. The act provided for the election of 152 delegates on February 4, 1861. Those elected assembled for their inaugural session at noon on Wednesday, February 13, in the Mechanics Institute at Capitol Square in Richmond, later moving their proceedings to the Capitol building.

By that time, states of the “Deep South,”–South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas–had adopted resolutions declaring themselves free and independent states and had met in Montgomery, Alabama, to consider forming a new confederacy. In Virginia, radical secessionists, known as “fire-eaters,” pressed the Old Dominion to follow their lead.

In February, the Confederate States of America took shape, and former U.S. Secretary of War Jefferson Davis chosen as its provisional president.

On April 4, an initial vote on secession in the Virginia Convention failed, 88 to 45. Days later came the attack on Fort Sumter in South Carolina, followed by President Abraham Lincoln’s call for 75,000 volunteers to “suppress the rebellion” in the Deep South. That proclamation galvanized secessionists and pushed many moderates toward their camp. Governor Letcher answered Lincoln in defiant terms: “You have chosen to inaugurate civil war.”

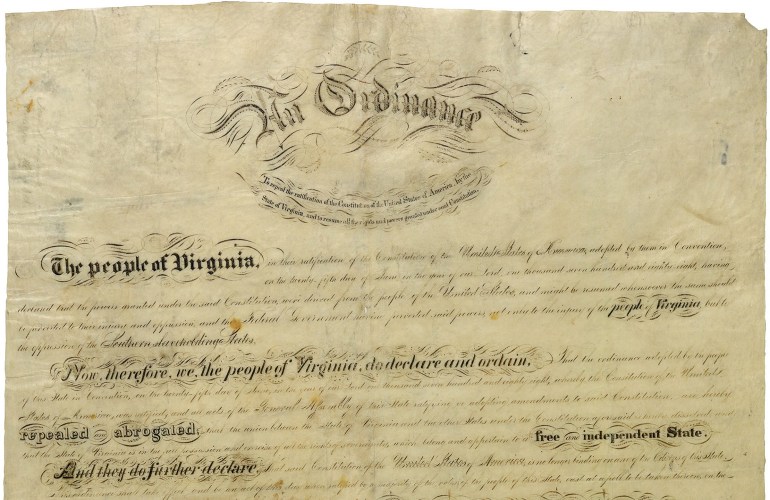

On Wednesday, April 17, the convention delegates approved “An ordinance to Repeal the ratification of the Constitution of the United States of America” by a vote of 88 to 55. The measure was made subject to ratification by popular vote on May 23, 1861. The Convention next passed a resolution expressing a desire to enter into an alliance with the Confederate States and placed control of Virginia’s militia in the hands of the Confederate president, and invited the Confederate government to move its capital to Richmond.

In the May 23 referendum, a majority of white, male voters over the age of 21 voted in favor, 125,950 to 20,373. Later accounting tallied the vote at 132,201 to 37,451.

In summary, Virginia’s secession was a multi-step process. Prominent Virginians organized what they believed to be a legally defensible and publicly legitimate method for the state to decide whether to remain in the Union. A convention of popularly elected delegates, which the General Assembly had nearly unanimously authorized, passed an ordinance repealing Virginia’s ratification of the U.S. Constitution. That action was, in turn, overwhelmingly approved in a popular referendum. Were they not carrying out the public will?

Unconditional unionists, concentrated in western Virginia, saw things differently. In their view, no legitimate process for leaving the Union existed, and therefore the Convention’s actions were illegal. They contended the May 23 referendum was illegitimate, marred by fraud and voter intimidation, and failed to reflect the popular will. They further believed that any public official who supported secession had vacated their office. These unionists, some of whom had been delegates to the State Convention, met in Wheeling in Virginia’s panhandle to organize a new state government that would remain loyal to the United States.

For most Virginians, however, the die had been cast, and their destiny would be decided alongside the other rebelling Southern states.

Sources

Freehling, William W. and Craig M. Simpson, ed. Showdown in Virginia: The 1861 Convention and the Fate of the Union. Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press, 2010.

Journals and Papers of the Virginia State Convention of 1861, Vol. 2. Richmond: Virginia State Library, 1966.

Lankford, Nelson D. “Virginia Convention of 1861.” Encyclopedia Virginia, December 7, 2020. https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/virginia-convention-of-1861/.

Reese, George H., ed. Proceedings of the Virginia State Convention of 1861, February 13-May 1, Vol. 1-4. Richmond: Virginia State Library, 1965.

Robertson, James I., Jr. “The Virginia State Convention of 1861” in Virginia at War 1861. Edited by William C. Davis and James I. Robertson Jr. Lexington, KY: The University Press of Kentucky, 2005.

Shanks, Henry T. The Secession Movement in Virginia, 1847–1861. Richmond: Garret & Massie, 1934.

The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Series I, Vol. II. With additions and corrections. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1902.

The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Series IV, Vol. I. With additions and corrections. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1902.