Another eyewitness account of the Engagement at Sewell’s Point appeared in the book The History of Norfolk, Virginia by Harrison W. Burton (1840-1902), a journalist who served in the 1st Virginia Infantry and Otey’s Battery during the Civil War. It was simply identified as being written by “a Georgia gentleman” shortly after the fight concluded, dated May 23, 1861.

NORFOLK, May 23, 1861.

“I must, in the beginning of the sketch, tell you that I am writing in the room where the British spy was stationed—where Lafayette stopped while in Virginia—where Tom Moore’s American poems were composed, including his ‘Maid of the Dismal Swamp’—the chamber where G. P. R. James wrote most of his romances. The table on which I write was the property of Lord Dunmore and used by him as a private writing desk. So you see I have decidedly the advantage of those who do their scribbling on camp stools. I am indebted for this special favor to one of Virginia’s most noble ladies, and here I would take occasion to say that Virginia ladies (particularly of Norfolk and Portsmouth) will live long in the memory of the Georgia troops.

“The Monticello, now the Star, lay with her broadside to the battery about three-quarters of a mile off. Our two thirty-two pounders had been mounted, and two rifled cannon peeped through their port-holes; and while the third gun was being ‘fixed up,’ Whiz-z-z came a shell, and bursted on our battery near Private Oliver Cleveland, who had gone out in front of one of our guns to shovel away sand. Captain Colquit (of Georgia, afterwards Gen. Colquit, and was killed at Gettysburg,) in command of the forces (consisting of parts of several Virginia companies and the City Light Guard, of Georgia), ordered the men to their posts, and in a few moments the welkin rang with the booming of our guns. The Monticello fired rapidly and bravely, but the most of her shots were wild. Some of them, however, were well directed, bursting in our embrasures, over our heads, and all around us. We learn that she has endeavored to make the impression that she passed the ordeal of our iron hail without injury; but she is slightly mistaken. Five holes are in her—the very best indication of which is her dreadful limping as she turned her stern to our fire, and hitched on a tug, which carried her off. We have no disposition to deal in falsehoods, and we tell the Monticello that some of her shots were well aimed, and furthermore, that she required heavy corking to save sinking, and that she must have lost many of her men. We hear but six are lost, but when the truth comes it will be double that number. If the Monticello is not crippled, we cordially invite her back to her old stand, near the buoy in front of our little sand bank.

“I wish to make mention of the brave and gallant bearing of Thad. Gray, of one of the Virginia companies (the Norfolk Juniors), during the engagement of Sunday, the 19th. In his bare skin to the waist, he worked like a Trojan—cool and self-possessed, unmoved by the enemy’s fire, he worked at his gun like a man and a brave soldier. Some of the men acted very conspicuous parts in the engagement, and deserve special notice. Sergeant Larin, Privates Mayo and Porter, in the hottest of the fire, took their spades and walked out in full view of the enemy, and at the most exposed points, and shoveled away sand which lay in front of two of the guns, obstructing the effect of their fire, and rendering them useless. Mr. J. Berrian Oliver, one of the most esteemed citizens of Georgia, was once buried in sand by the bursting of a shell in the embrasure of the gun at which he was working. Before the smoke and dust had cleared away, he was at his post unmoved and undaunted. Inexperienced in military life, he has won rich laurels in this, the first battle on Virginia soil. A braver and purer spirit never marched to meet an enemy. Lieutenant Maffit, who commanded one of the guns, acted with a degree of bravery and coolness that would have done credit to an older and more experienced soldier.

“Captain Lamb well sustained the reputation of Virginia’s blood and bravery. Captain Colquit, of the City Light Guards, commanding, acted with the most remarkable degree of self-possession, wisdom and bravery, assisting under the thick hail of shell and shot in planting the flag of Georgia upon the ramparts—the beautiful flag presented to the City Light Guards by Miss Ellen Ingraham, of Columbus, one of the most beautiful and lovely daughters of Georgia. Well may she feel proud at that beautiful banner, for it waved in triumph at the second battle of the Confederate States. Major Taylor mounted the ramparts and waved it high in the air as the Monticello moved off.”

Assuming the letter is genuine, it is an invaluable record of what occurred, written only a few days after the engagement when the events were undoubtedly still fresh in the author’s mind.

It’s notable that he mentioned Pvt. Thaddeus “Thad” S. Gray (1826-1895) as belonging to the Norfolk Juniors, contradicting Gray’s obituary in the Norfolk Virginian (which said he was a member of the Woodis Rifles before later joining the 12th Virginia Infantry).

The author also mentioned others in the engagement. “Sergeant Larin” likely refers to Sgt. Albert Moses Luria (1843-1862). Privates Mayo and Porter were Zachariah N. Mayo (1837-1872) and Albert Porter. Luria went on to become a lieutenant in the 23rd North Carolina and was mortally wounded at the Battle of Seven Pines.

What was the Georgian flag planted on the ramparts “the beautiful flag presented to the City Light Guards by Miss Ellen Ingraham, of Columbus”? It was presented on the first Sunday of February 1861 at Temperance Hall in Columbus, Georgia by Ella Rose Ingram (1839-1922), also spelled Ingraham. Ella later married Major Walter H. Weems of the 6th Alabama and later colonel of the 64th Georgia Infantry.

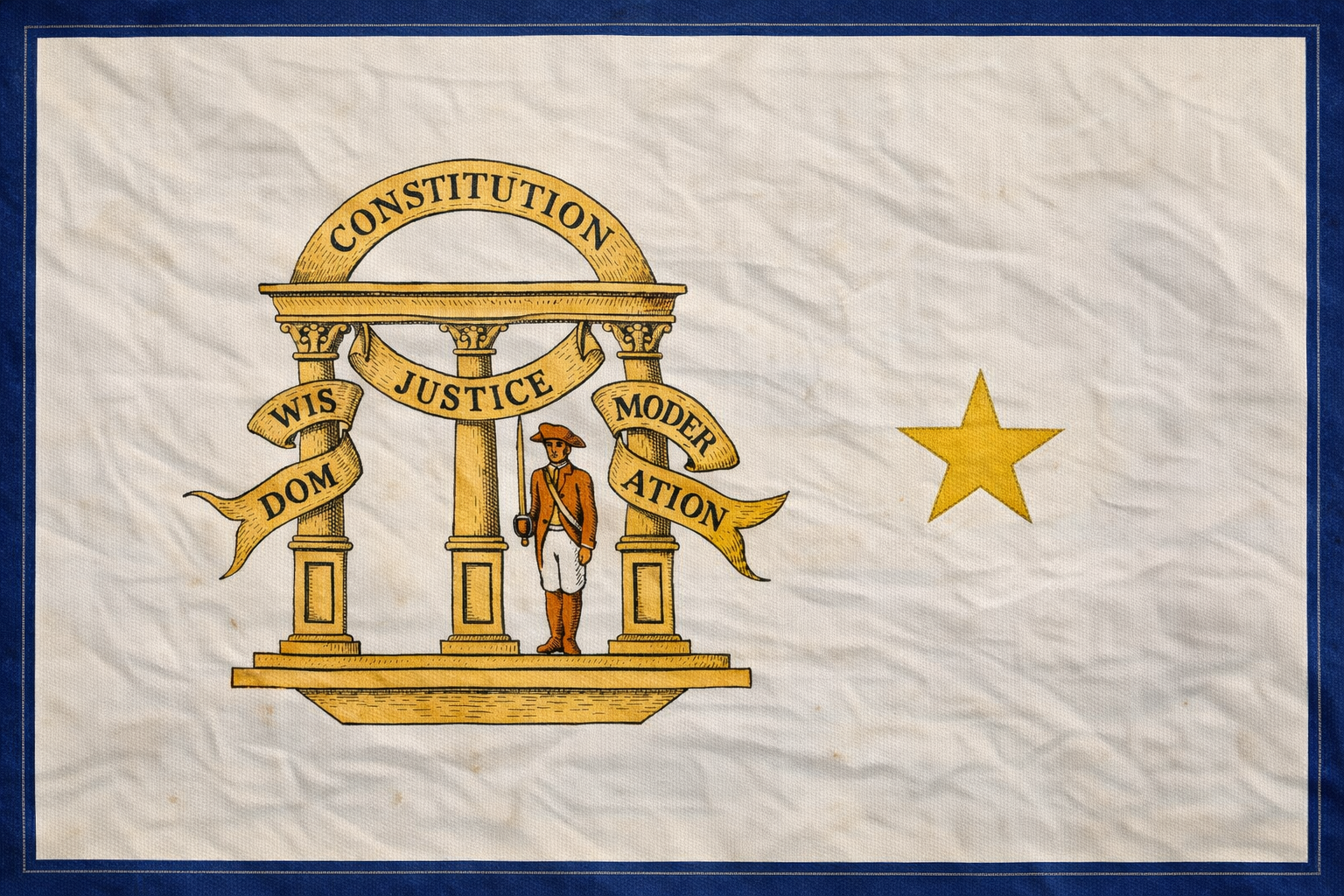

I’ve been unable to confirm the flag’s design, other than the following description from this website: “white field with blue trim; Georgia coat-of-arms on obverse together with a single star; Goddess of Liberty personified on reverse side.”

The colors of Georgia’s flag were not standardized at the time, and few surviving examples remain. Captain Henry Eagle’ report of May 19, 1861, stated, “The rebels immediately hoisted a white flag, with some design on it…” Devereaux D. Cannon, in The Flags of the Confederacy: An Illustrated History (1994), noted that the flag raised over the capitol in Milledgeville “has been described as the arms of Georgia on a white field.”

The following is the flag of the Columbus City Light Guard as imaged by ChatGPT, based on these descriptions.

Sources

“Albert Moses Luria. Gallant Young Confederate.” American Jewish Archives 7 (January 1955): 90-103.

Burton, H.W. The History of Norfolk, Virginia. Norfolk: Norfolk Virginian Job Print, 1877.

Cannon, Devereaux D. The Flags of the Confederacy: An Illustrated History. Gretna: Pelican Pub. Co., 1994.

“Georgia Flag in First Fight,” The Atlanta Constitution (Atlanta, GA) 4 May 1904.

Hewett, Janet B., ed. Georgia Confederate Soldiers, 1861-1865, Vol. II. Wilmington: Broadfoot Publishing Company, 1998.

Stewart, William H. A Pair of Blankets: War-Time History in Letters to the Young People of the South. New York: Broadway Publishing Co., 1911.

“The Flag Presentation,” Daily Columbus Enquirer (Columbus, GA) 4 February 1861.

One thought on “Eyewitness Account of the Engagement at Sewell’s Point by a Member of the Columbus City Light Guard”