One of the fun aspects of studying history is imagining how events might have unfolded differently. The consequences of those changes can range from trivial to altering the course of an entire war.

A major “what if” of the early Civil War is how the First Battle of Bull Run might have unfolded if Joseph E. Johnston’s Army of the Shenandoah had not arrived in time to reinforce P. G. T. Beauregard. Would the battle have become a Confederate defeat? Could the war have ended then and there?

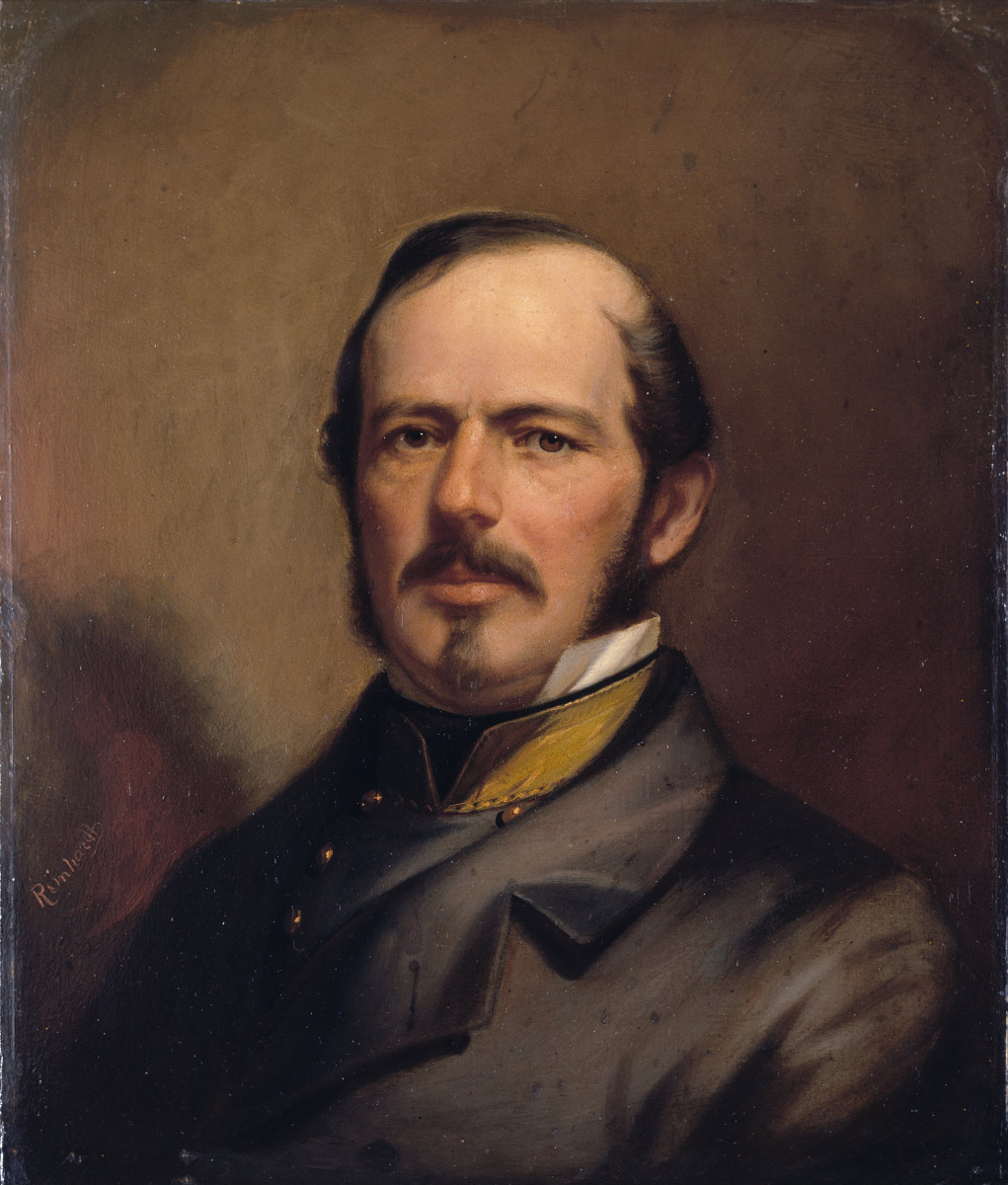

In fact, the battle ended in a Confederate victory, and in the wake of the disaster the Congressional Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War laid blame on Maj. Gen. Robert Patterson for failing to keep Johnston’s army in the Shenandoah Valley.

In reality, it is unlikely Patterson could have done much more than he did. Most of his army consisted of 90-day volunteers whose enlistments were due to expire within days. Their uniforms were falling apart, morale was low, and only a few regiments agreed to stay on past their term of service. Patterson’s senior commanders agreed with his assessment of the situation and supported his actions.

Patterson also repeatedly maintained that he would have attacked Johnston’s army at Winchester if given an explicit order. Winfield Scott’s instructions had been vague and sometimes contradictory, leaving Patterson’s movements to his discretion on the one hand while expecting to hear of Johnston’s defeat on the other. The aging general-in-chief was clearly distracted by events unfolding in northeastern Virginia.

What if Scott had issued direct orders to attack? Could Patterson have defeated Johnston, or at least kept him in the Shenandoah Valley long enough to avert disaster at Bull Run? Or could Johnston have defeated Patterson and still reached Manassas in time to influence the battle?

To address these questions, it is helpful first to establish a detailed timeline of events. As the chronology below shows, there was very little margin in which any alternative scenario could have played out. Only five full days passed between the time Patterson’s army reached Bunker Hill on July 15 and the First Battle of Manassas / Bull Run on July 21.

- 15 July – Patterson’s army reaches Bunker Hill, 12 miles north of Winchester.

- 16 July – Patterson’s army rests at Bunker Hill.

- 17 July – Patterson moves to Charlestown, 11.7 miles east of Bunker Hill and about 21 miles northeast of Winchester.

- 18 July – Johnston receives a telegram at 1 a.m. instructing him to unite with Beauregard at Manassas Junction “if practicable.” Later that morning, his army begins moving toward Piedmont Station (today Delaplane), 25 miles southeast of Winchester. At 1 p.m., Patterson telegraphs Washington, D.C., “I have succeeded, in accordance with the wishes of the General-in-Chief, in keeping General Johnston’s force at Winchester.”

- 19 July – Johnston’s lead brigade under Thomas J. Jackson reaches Piedmont Station at 9 a.m. and arrives at Manassas Junction by train around 4 p.m.

- 20 July – Johnston reaches Manassas Junction about noon. Nine regiments and a battalion are delayed due to suspected railroad sabotage and do not reach Manassas until after the battle.

- 21 July – First Battle of Bull Run.

Best Case Scenario for the North

A major Union victory forces Johnston to retreat deeper into the Shenandoah. Beauregard stands alone against McDowell at Manassas and is defeated.

In mid-July, Patterson asked his 90-day regiments whether they would remain beyond their enlistment. Only a few agreed. But what if, with the prospect of battle looming, the opposite had happened? If the 90-day men, who made up most of his army, had enthusiastically chosen to stay and fight, could they have carried the day?

In Trans-Allegheny Virginia, George McClellan had already shown what could be achieved with superior numbers, even with untested troops. Patterson might have used his strength the same way: fixing Johnston with demonstrations along his front while sending a flanking force to turn his position. If he cut Johnston’s route east, the Army of the Shenandoah would have been driven south up the Valley, leaving Beauregard without reinforcements at Bull Run.

Though not a decisive knockout, twin Union victories in the Valley and at Manassas would have given the North a powerful morale boost, dealt a serious early setback to the Confederate war effort, and eroded support for the Confederate government.

Best Case Scenario for the South

A major Confederate victory allows Johnston to both defeat Patterson’s army and come to Beauregard’s aid. The dual loss significantly sets back the Union war effort in the Eastern Theater.

As he moved toward Charlestown (Charles Town), Patterson’s army was already coming apart. On July 18, he reported, “I to-day appealed almost in vain to the regiments to stand by the country for a week or ten days. The men are longing for their homes, and nothing can detain them.” Their uniforms were in tatters, and some new regiments arrived without arms. Under these conditions, attacking fortified positions would have been difficult at best and suicidal at worst.

What if Winfield Scott had issued a direct order to attack and Patterson had hurled his demoralized, inexperienced regiments against Johnston’s well-prepared defenses? The result could have been a catastrophe, with his men breaking under withering artillery and musket fire. The defeat might have been so lopsided that Johnston felt secure leaving Winchester’s defenses to the militia and departing for Manassas on roughly the same schedule as he did historically. It is possible, though still unlikely.

Most Likely Outcome

A minor Confederate victory clears the lower Shenandoah Valley of Federal troops but Johnston is not able to reach Manassas in time. Beauregard stands alone against McDowell and is defeated.

The Battle of Big Bethel offers a compelling forecast of the probable results had Patterson attacked Johnston’s forces behind their earthworks north of Winchester. During the confrontation at Big Bethel on June 10, a Union force of 4,500 men, organized into seven regiments, assaulted 1,670 Confederates who were defending hastily constructed breastworks. The engagement resulted in a casualty ratio of 1-to-7.6, overwhelmingly in the Confederates’ favor.

A similar outcome could have been expected at Winchester. Patterson’s inexperienced regiments would have had to advance across open terrain, subjected to artillery fire from five batteries and additional heavy guns. Although Johnston’s troops were also green, they would have held the significant advantage of fighting from behind protective cover. Jackson’s brigade had already demonstrated discipline under fire at the Battle of Hoke’s Run.

At Winchester, Johnston’s army was further reinforced by approximately 2,500 Virginia militia under the command of Brigadier Generals G. S. Meem and J. H. Carson. While these units may not have been in fighting condition, their presence would have allowed Johnston to free up better organized and equipped regiments for deployment in critical areas of the battle.

It is likely that Patterson would have initiated the assault with probing attacks led by his most dependable troops. Even if these formations had managed to hold together under the inevitable artillery barrage, they would have almost certainly been repelled at the Confederate defensive works, suffering disproportionately high casualties in the process.

But could Johnston have fought this battle, won, and extracted himself in time to help Beauregard at Bull Run? It’s theoretically possible but unlikely.

Suppose that instead of resting at Bunker Hill, Patterson had advanced to Winchester and fought a battle on July 17. The next day, Johnston’s army would have been exhausted. Wounded men would require care, ammunition would need to be replenished, and regiments reorganized and rested. Even if the Confederates won, there was no guarantee Patterson’s army would withdraw completely, so Johnston would still have to worry about a renewed attack.

Even in the actual timeline, when Johnston began his movement to Manassas on July 18, about a third of his army failed to reach the battlefield in time. It is possible he might have sent only one or two brigades east, gambling that he did not need his full force to keep Patterson in check. He later wrote that he believed Meem’s and Carson’s militia were enough to hold Winchester, assuming Patterson would simply follow him wherever he went.

So it is conceivable that part of Johnston’s army might still have reached Manassas in time to take part in the battle. Would that have been enough? It is difficult to say. It seems likely Beauregard would still have been forced to withdraw in the face of McDowell’s superior numbers.

Sources

Davis, William C. Battle at Bull Run: A History of the First Major Campaign of the Civil War. Mechanicsburg: Stackpole Books, 1977, 1995.

Detzer, David. Donnybrook: The Battle of Bull Run, 1861. Orlando: Harcourt, Inc., 2004.

Gottfried, Bradley M. The Maps of First Bull Run: An Atlas of the First Bull Run (Manassas) Campaign, Including the Battle of Ball’s Bluff, June – October 1861. New York: Savas Beatie, 2009.

Longacre, Edward G. The Early Morning of War: Bull Run, 1861. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2014.

Patterson, Robert. A Narrative of the Campaign in the Valley of the Shenandoah in 1861. Philadelphia: John Campbell, 1865.

The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Series I, Vol. II. With additions and corrections. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1902.