Did the so-called “Skirmish at Arlington Mills” really happen? Learn how a simple newspaper error sparked a century-long myth about one of the Civil War’s first land engagements. Primary sources reveal conflicting accounts, misidentified locations, and a puzzling lack of Confederate testimony—raising questions about how historical narratives take shape and why verifying sources is essential to getting history right.

A lonely Civil War Trail sign along Columbia Pike in Arlington, Virginia, reads: “On the night of June 1, 1861, a scouting party of Virginia militia attacked U.S. troops at Arlington Mill, which stood to your right. Co. E 1st. Michigan Volunteer Infantry Regiment was on picket duty at the mill guarding the Columbia Turnpike and the Alexandria, Loudoun, & Hampshire Railroad. In a nearby house, Co. G, of the 11th New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment (1st New York Fire Zouaves), prepared to relieve the Michigan men. At about 11 P.M. the Virginians fired at the pickets, killing one and wounding another. The militiamen were driven off after a brief exchange of fire, with one man wounded. The ‘Skirmish at Arlington Mills‘ as the New York Times called it, was among the first military engagements of the Civil War.”

But did this actually happen? A thorough review of primary sources casts serious doubt. The date, location, and even the attack itself may be completely inaccurate, raising the question of how much we take for granted as true about this early period of Civil War history. What happens when historians get it wrong?

Background

On the morning of May 24, 1861, the invasion of northeast Virginia began. Union regiments crossed the Potomac River and occupied Arlington Heights and Alexandria without opposition. The 1st Michigan Infantry Regiment, led by Col. Orlando B. Willcox; 11th New York Infantry Regiment (Ellsworth Zouaves), led by Col. Elmer E. Ellsworth; a section of artillery, and a company of cavalry occupied Alexandria. Ellsworth was killed in a showdown with a hotel proprietor, leaving Willcox in overall command. Confederate Capt. Mottrom Dulany Ball and about 35 of his Fairfax Cavalry were captured.

The two infantry regiments went into camp on Shuter’s (Shooter’s) Hill, just west of town along the Little River Turnpike (today Duke Street), where they began constructing Fort Ellsworth in honor of the fallen colonel. Shuter’s Hill is the present-day location of the George Washington Masonic National Memorial. Shortly after, the 1st Michigan and 11th New York established a picket post at nearby Cloud’s Mill.

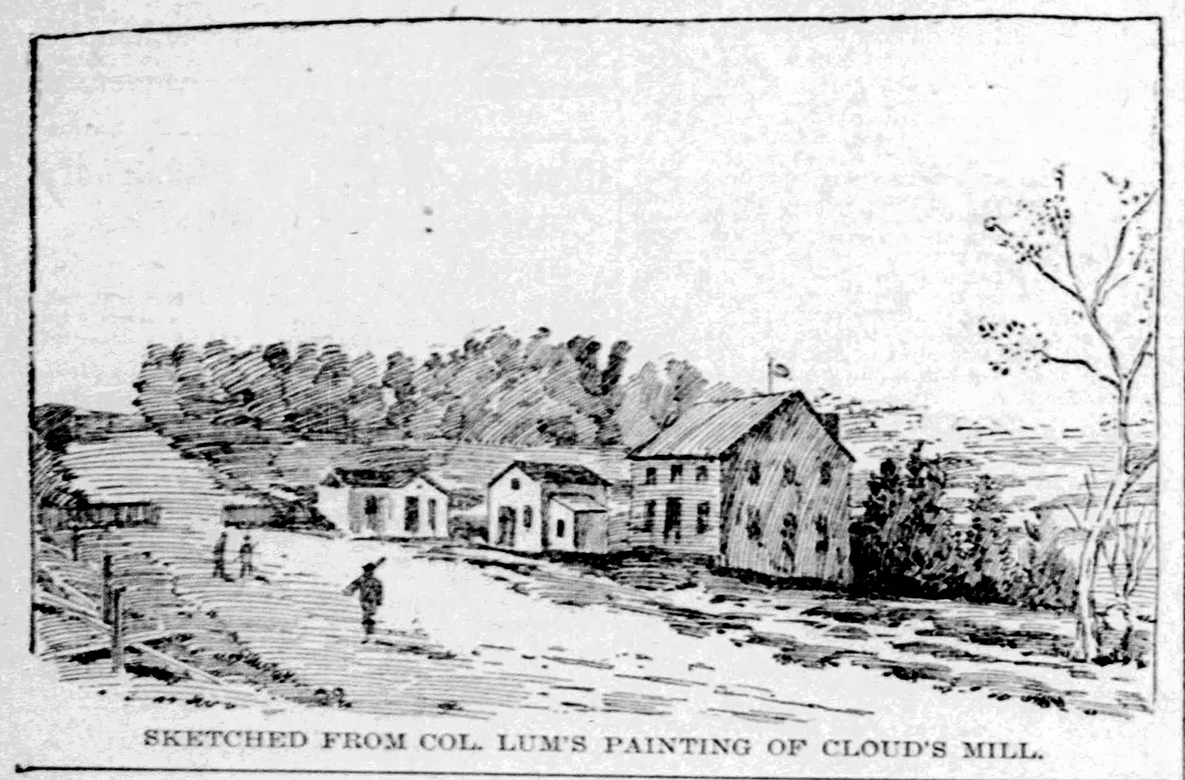

The mill owned by James Cloud, built between 1813 and 1816, was located approximately three miles west of Shuter’s Hill on the north side of Little River Turnpike, near Holmes’ Run. It was described as an unremarkable, four-story brick building, “noted for nothing but the millions of horrible fleas bred in its vicinity,” its wheel turned by a muddy stream mostly hidden by weeds and brush. Sometime near the end of May, Captain Ebenezer Butterworth and Company C, 1st Michigan, the “Coldwater Cadets” seized the mill and carried off 400 barrels of flour and hundreds of bushels of wheat.

It was a logical place for a picket post for these two regiments. It was about an hour walk from their camp, along the main road to Anandale and Fairfax Court House. It provided shelter in inclement weather, allowed them to over watch the road, and controlled the means of producing foodstuffs for hungry troops. Following the war, veterans of the 1st Michigan looked back fondly on their watchful nights at the mill. Charles F. Lum, late of the “Detroit Light Guard,” even created a painting of the mill for an 1896 reunion.

Which Mills?

Northern newspaper correspondents, unfamiliar with northeastern Virginia, confused Cloud’s Mill and Arlington Mills. Arlington Mills was a well-known grist mill on Four Mile Run in Arlington County and a prominent landmark along the Columbia Turnpike. Robert E. Lee’s father-in-law, George Washington Parke Custis, had owned the mill (he died in 1857), leading to the misconception among Union troops that Lee owned it. It was located approximately four miles west of Long Bridge, five miles northwest of Alexandria, and 12 miles east of Fairfax Court House.

On June 1, 1861, the New York Daily Herald initially reported that the “Michigan Regiment” (1st Michigan) captured hundreds of barrels of flour at Arlington Mills–a report that appeared in newspapers across the country. The next day, it correctly reported that the flour was actually captured at Cloud’s Mills. After all, why would the 1st Michigan raid a mill located six miles north of its camp, when others were much closer?

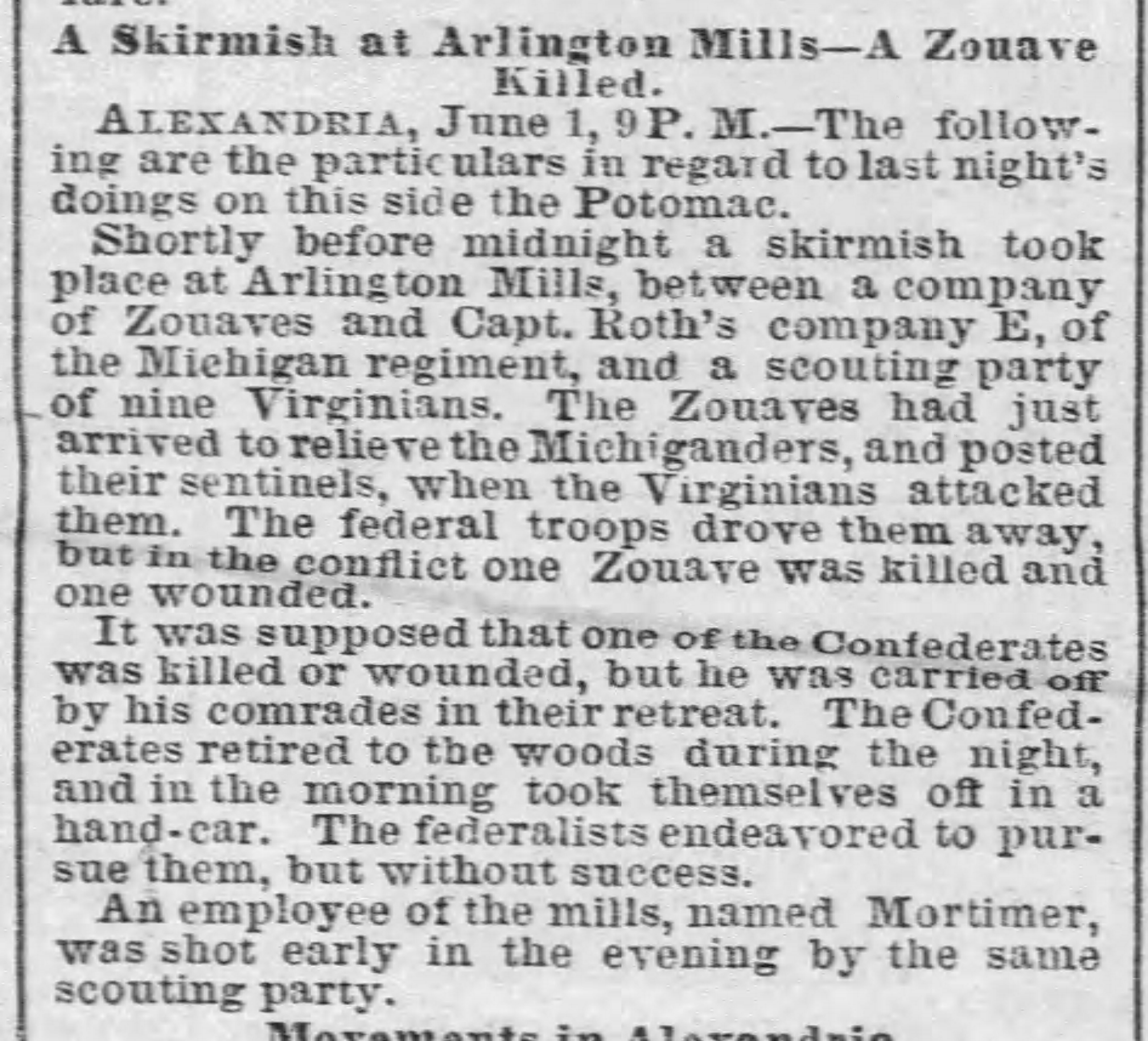

Likewise, articles like the following appeared in newspapers across the country reporting a skirmish between secessionists and men from the 1st Michigan and New York Zouaves at Arlington Mills:

Those early reports were untrue. On June 2, 1861, the New York Daily Herald published the following, correcting the location of the skirmish in which Henry Seeley Cornell (sometimes Henry C. Cornell) of the Zouaves was killed:

And this article appeared in the Nashville Union and American, June 6, 1861:

Despite multiple references to Cloud’s Mill appearing in subsequent articles about this incident, the initial misreported location stuck. There are references to a “Skirmish at Arlington Mills” not only on a Civil War Trail sign, but in modern books and websites, and the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies published by the War Department.

When Did this Skirmish Occur?

The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Series I, Vol. II lists among its summary of principal events: June 1, 1861 — Skirmishes at Arlington Mills and Fairfax Court-House, VA. The Arlington Mills Civil War Trail sign states that the skirmish occurred around 11p.m. the night of June 1st. Once again, the fog of war is to blame.

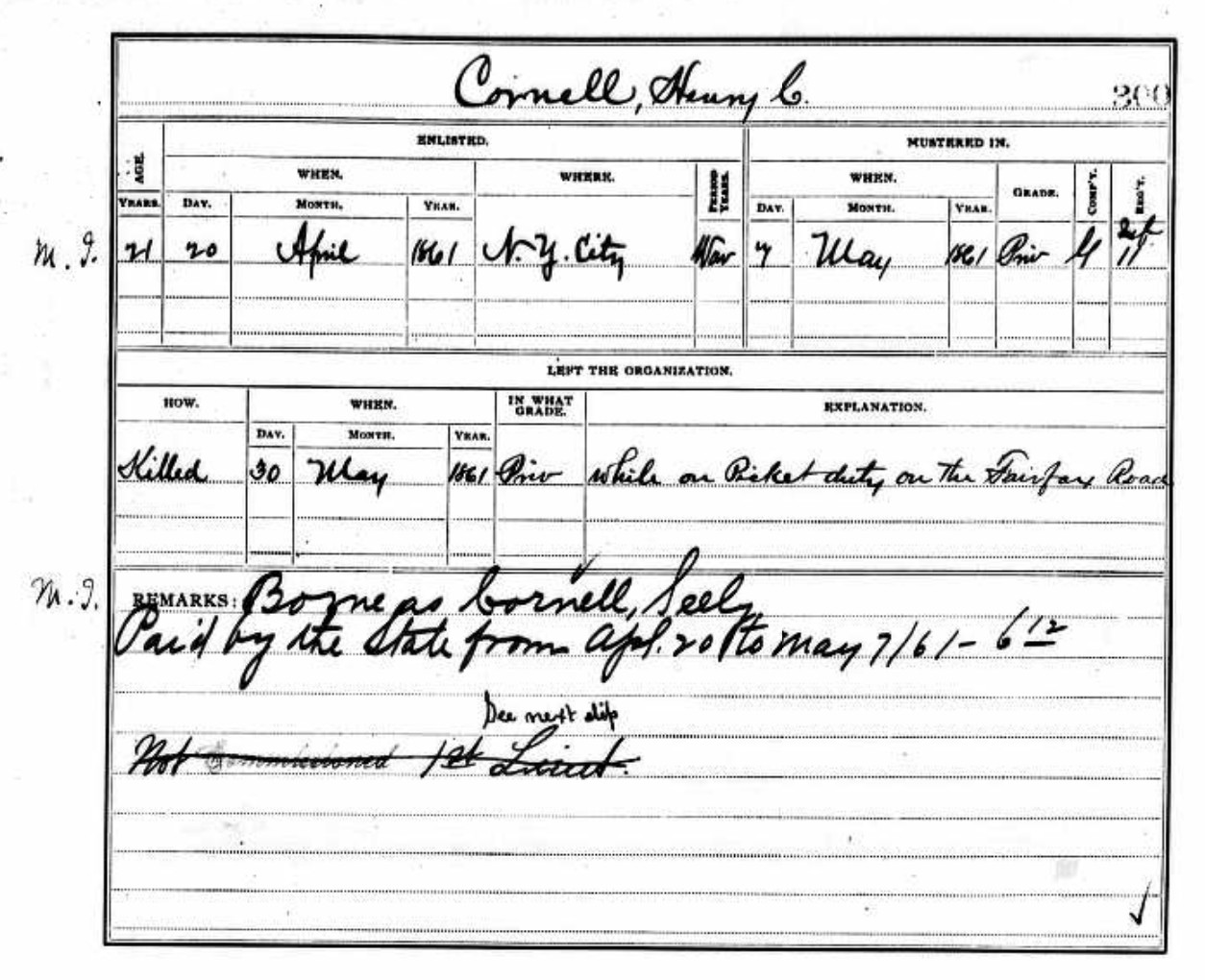

In fact, contemporary newspapers reported the skirmish as occurring shortly before midnight on Friday, May 31, 1861. The following funeral notice for Henry S. Cornell in the New York Herald clearly states that he died on May 31st, as did a metal plate attached to his coffin:

The New York Civil War Muster Roll Abstract, as well as his headstone (which looks new), lists his date of death as May 30, 1861, but I don’t believe that to be accurate. There are no contemporaneous sources that say he was killed on the 30th. They nearly all state “Friday” or “last night” (if datelined on June 1st), which was May 31st.

The discrepancy in dates underscores how easily historical events can become muddled, even in official records. While the War Department placed the skirmish on June 1, contemporary sources—funeral notices, newspaper reports, and firsthand accounts—consistently point to May 31. This misalignment, likely the result of clerical errors or misinterpretations, demonstrates how quickly misinformation can become entrenched in historical narratives. Correcting these details is more than an academic exercise; it is essential for preserving an accurate record of the past and understanding how the war unfolded in its earliest days.

Was there a Skirmish? A Dog in the Nighttime Problem

We know beyond a reasonable doubt that this incident took place on the night of May 31st at Cloud’s Mill, but a third question remains: Was it a skirmish? This is an example of what’s known as a dog in the nighttime problem, famously illustrated in Arthur Conan Doyle’s short story “Silver Blaze”:

“Is there any other point to which you would wish to draw my attention?”

“To the curious incident of the dog in the night-time.”

“The dog did nothing in the night-time.”

“That was the curious incident,” remarked Sherlock Holmes.

I can count on one hand the number of Civil War skirmishes with entirely one-sided accounts. In fact, the only example that comes to mind—an incident at Red House on the Kanawha River—turned out to be a case of friendly fire. Through my research into the small skirmishes and battles of the war’s opening months, I’ve found that even the most obscure engagements typically have at least one mention in a newspaper, diary, letter, or report from either side. However, when it comes to the skirmish at Cloud’s Mill, I have yet to find a single Confederate source that doesn’t rely on Northern accounts to describe what happened.

All the more curious, considering this took place just days after the occupation of Alexandria. Since the skirmish at Fairfax Court House occurred the following day, this would have been among the first land engagements of the Civil War. Surely someone involved would have come forward to boast about giving the “Yankee invaders” their first bloody nose, if not in 1861, than after the war?

Something undoubtedly happened at Cloud’s Mill that night. Twenty-one-year-old Henry S. Cornell was killed, and William Cushman was wounded. Cushman, “who was shot at the mill,” is listed in a hospital report published in the New York Atlas, June 16, 1861. Private Arthur O’Neil Alcock, Company A, a former newspaper editor, sent long missives to the New York Atlas and New York Leader detailing the Fire Zouaves’ first campaign. Unfortunately, the letter covering the period during which Henry Cornell was killed got lost in the mail and was never printed.

However, in a letter published in the New York Leader, July 3, 1861, under the pseudonym Harry Lorrequer, Alcock wrote [emphasis mine]: “The simple fact is, that since we left New York we have had only one man killed and two wounded, as is said, by the fire of the rebels. And it is by no means certain that these were not shot by friends in mistake, or by themselves accidentally or through carelessness.”

Then there was the following paragraph reprinted from a New York newspaper that appeared in the Philadelphia Inquirer, June 7, 1861:

If Cornell and Cushman were shot by the enemy rather than accidentally by their own men, who was responsible? What Confederate unit was involved? The possibilities are limited, as only a handful of companies were in the area at the time. The Warrenton Rifles, Rappahannock Cavalry, and Prince William Cavalry were stationed at Fairfax Court House. However, both cavalry companies were poorly armed and unable to participate in the skirmish there on June 1. The Warrenton Rifles had just arrived on the 31st. The Goochland and Hanover Light Dragoons were at Fairfax Station, 3.5 miles south, while the remaining units were at Manassas Junction.

Because the skirmish at Fairfax Court House took place the very next day, June 1, 1861, we have extensive records detailing the disposition of Confederate troops. Unlike the incident at Cloud’s Mill, there are numerous Union and Confederate accounts of what transpired at Fairfax Court House. Yet, in his recollection of the prior evening, William “Extra Billy” Smith, a former governor of Virginia, makes no mention of any movement toward Union lines. When U.S. cavalry approached Fairfax Court House on the morning of June 1, they encountered a small group of Confederate pickets, capturing some while the rest fled. The remaining Confederates were asleep when the alarm was raised.

The presence—or absence—of Confederate forces is the dog in the nighttime problem. If no uniformed Confederate volunteers were in the vicinity of Cloud’s Mill on the night of May 31, 1861, only two possibilities remain: an attack by local civilians or friendly fire. The simpler and more likely explanation is that, in the darkness and confusion, with raw recruits navigating unfamiliar enemy territory and perceiving threats at every turn, Union pickets mistakenly fired on each other. But without additional evidence, we may never know for certain.

Sources

Beiro, Jean A. A History of Cloud’s Mill in Alexandria, Virginia. Edited by John G. Motheral. Alexandria: Alexandria Archaeology Publications, 1986.

Bell, John W., ed. Memoirs of Governor William Smith, of Virginia: His Political, Military, and Personal History. New York: The Moss Engraving Company, 1891.

Connery, William S. Civil War Northern Virginia 1861. Charleston: The History Press, 2011.

Isham, Frederic S., ed. History of the Detroit Light Guard: Its Records and Achievements. Detroit: Detroit Light Guard, 1896.

Musick, Michael P. 6th Virginia Cavalry. Lynchburg: H.E. Howard, Inc., 1990.

Schroeder, Patrick A. and Brian C. Pohanka, eds. With the 11th New York Fire Zouaves in Camp, Battle, and Prison: The Narrative of Private Arthur O’Neil Alcock in the New York Atlas and Leader. Lynchburg: Schroeder Publications, 2011.

Scott, Robert G., ed. Forgotten Valor: The Memoirs, Journals, & Civil War Letters of Orlando B. Willcox. Kent: Kent State University Press, 1999.

Styple, William B., ed. Writing and Fighting the Civil War: Soldier Correspondence to the New York Sunday Mercury. Kearny, NJ: Belle Grove Publishing Company, 2000.

Wenzel, Edward T. Chronology of the Civil War in Fairfax County, Part I. CreateSpace: By the Author, 2015.

3 thoughts on “Which Mills? Decoding an Early Civil War Skirmish”