In the twilight hours of May 24, 1861, Union forces crossed the Potomac into Virginia, marking the first federal invasion of Confederate territory. As troops secured key locations in Alexandria, Colonel Elmer E. Ellsworth, a rising star and personal friend of President Lincoln, led his Fire Zouaves into the city—only to meet a tragic fate at the hands of an enraged innkeeper. This dramatic moment set the stage for the brutal conflict to come.

In late April and early May of 1861, a tense standoff between federal forces and the Commonwealth of Virginia threatened to escalate into full-scale war. On April 17, 1861, delegates at the Virginia Secession Convention in Richmond passed an ordinance of secession, contingent on the outcome of a popular referendum scheduled for May 23. In response, U.S. President Abraham Lincoln extended the naval blockade to include Virginia’s ports, and skirmishes erupted between Virginia shore batteries and U.S. Navy ships.

Despite the growing tensions, there remained a possibility that Virginia voters would reject secession. Pro-Union delegates, who had returned to western Virginia from Richmond, clung to that hope and organized their own convention in Wheeling along the Ohio River. Meanwhile, pro-secession leaders, including the reluctant Governor John Letcher, acted as though Virginia had already become an independent nation. Shortly before the referendum, they accepted an offer to make Richmond the new capital of the Confederate States of America.

Philip St. George Cocke (1809–1861), a wealthy plantation owner and West Point graduate (Class of 1834), was among the first to volunteer his services to the Virginia government. Governor John Letcher appointed him as a brigadier general in the Virginia Provisional Army, tasking him with organizing and commanding the Alexandria Line—the state’s primary defensive position against potential northern invasion. However, when Virginia decided to reduce the number of its general officers, Cocke was administratively demoted to colonel—a perceived insult he never forgot. He established his headquarters at Culpeper Court House and set to work organizing the local militia.

Between 1791 and 1846, the town of Alexandria, Virginia (population 12,652 in 1860), was part of Washington, D.C., but was retroceded to Virginia, largely due to concerns that slavery might be abolished in the District. The slave trade was highly profitable in Alexandria, which had a deep-water port on the Potomac River and served as a major trading hub. Since April 1861, James W. Jackson, proprietor of the Marshall House inn, had defiantly flown a large Confederate “Stars and Bars” flag from a 40-foot pole on the roof. In the May 23 referendum, Alexandria overwhelmingly voted for secession, with 958 in favor and 106 opposed.

As overall commander of Virginia’s Provisional Army, Robert E. Lee sought to avoid provoking a federal invasion of northeastern Virginia. His strategy included refraining from stationing troops or constructing defenses along the Potomac River below Washington, D.C. Instead, sentries guarded the bridges, and a few companies garrisoned Alexandria. On May 21, Lee placed Brigadier General Milledge Luke Bonham (1813–1890), a South Carolina congressman, in command of the Alexandria Line. “It is proper for me to state to you that the policy of the State at present is strictly defensive,” Lee counseled. “…Alexandria in its front will, of course, claim your attention as the first point of attack, and, as soon as your force is sufficient, in your opinion, to resist successfully its occupation, you will so dispose it as to effect this object, if possible, without appearing to threaten Washington City.”

The following units of Virginia militia were stationed in and around Alexandria on the morning of May 24, 1861:

Col. George H. Terrett, Commanding

| Unit | Commander | Strength |

|---|---|---|

| 6th Battalion, Virginia Volunteers | Maj. Montgomery D. Corse | 430 (est.) |

| Fairfax Cavalry (Washington’s Home Guards) | Capt. Edward B. Powell | 30 |

| Fairfax Cavalry (Chesterfield Troop) | Capt. Mottrom D. Ball | 40 |

| 500 |

If the Union Army did invade northeastern Virginia, there were four possible points of entry:

- Chain Bridge – Chain Bridge was a wooden crossbeam truss structure spanning the Potomac River below Little Falls, approximately 3.5 miles northwest of Georgetown University. It got its name from the chain suspension bridge built there in 1808. The wooden structure standing in 1861 was erected ten years earlier.

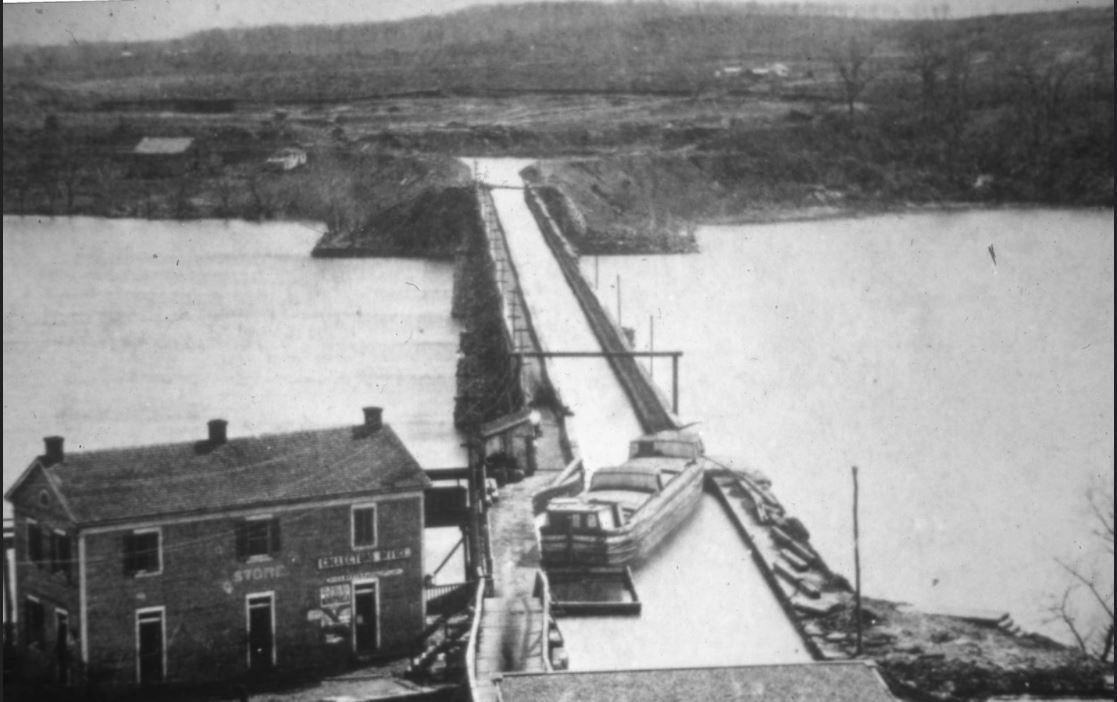

- Aqueduct Bridge – The Aqueduct Bridge, completed in 1843, allowed boats to cross from the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal to the Alexandria Canal. There was a narrow walkway for foot traffic over the bridge, so troops crossing had to march in a single file line.

- Long Bridge – Long Bridge, a timber pile structure 5,000 feet in length, was the most direct crossing from Washington, DC. It was originally known as Washington Bridge and opened in 1809. In 1861, railroad tracks approached it from either side, but did not cross. Today, it is exclusively a railroad bridge.

- By boat – The fastest approach to Alexandria was across the water. The USS Pawnee, a steam-powered sloop-of-war, had been anchored off shore since May 11th, overwatching the town. When U.S. volunteers eventually landed in Alexandria, they were ferried across by the steamers Baltimore, Mount Vernon, and James Guy.

When Virginia voters overwhelmingly endorsed secession in the May 23rd referendum, it removed all doubt over what direction events would take. Ten volunteer regiments, two U.S. cavalry companies, and a battery of artillery were already lined up along the north shore of the Potomac River, waiting for orders.

The expedition consisted of the following units, plus a few staff officers and U.S. Army engineers:

Brig. Gen. Joseph K. F. Mansfield, Commanding Department of Washington

Maj. Gen. Charles W. Sandford, Commanding New York Militia

Brig. Gen. Theodore Runyon, Commanding New Jersey Brigade

| Unit | Commander | Strength | Crossed at |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st Battalion, District of Columbia Militia | Maj. James McHenry Hollingsworth | 270 | Aqueduct Bridge, Chain Bridge (Co. A) |

| National Rifles, the Constitutional Guards, and the Washington Light Infantry Battalion, Company E | Col. Charles P. Stone | 180 (est) | Long Bridge |

| 69th Regiment, New York State Militia | Col. Michael Corcoran | 1,050 | Aqueduct Bridge |

| 28th Regiment, New York State Militia | Lt. Col. Edward Burns | 563 | Aqueduct Bridge |

| 5th Regiment, New York State Militia | Col. Christian Schwarzwaelder | 600 | Aqueduct Bridge |

| 7th Regiment, New York State Militia | Col. Marshall Lefferts | 1,050 | Long Bridge |

| 25th Regiment, New York State Militia | Col. Michael K. Bryan | 500 | Long Bridge |

| 12th Regiment, New York State Militia | Col. Daniel A. Butterfield | 900 | Long Bridge |

| 2nd New Jersey Infantry Regiment | Col. Henry M. Baker | 750 | Long Bridge |

| 3rd New Jersey Infantry Regiment | Col. William Napton | 780 | Long Bridge |

| 4th New Jersey Infantry Regiment | Col. Matthew Miller | 784 | Long Bridge |

| 11th New York Infantry Regiment (Ellsworth Zouaves) | Col. Elmer E. Ellsworth | 1,079 | By boat on steamers Baltimore, Mount Vernon, and Guy |

| 1st Michigan Infantry Regiment | Col. Orlando B. Willcox | 780 | Long Bridge |

| 2nd United States Cavalry, Company B | Lt. Charles H. Tompkins | 75 | Aqueduct Bridge |

| 2nd United States Cavalry, Company I | Capt. Albert G. Brackett | 75 | Long Bridge |

| 2nd United States Cavalry, Company E | Lt. John J. Sweet | 76 | Long Bridge |

| 3rd United States Artillery, Light Company E (Sherman’s Battery) | Capt. Romeyn B. Ayres | 4 guns | Long Bridge |

| 14th New York State Militia, Corps Engineers | Capt. R. Burt | 48 | Aqueduct Bridge |

| President’s Mounted Guards | Capt. S. W. Owen | Long Bridge (part), Aqueduct Bridge (part) | |

| Approx. 9,560 |

On the night of May 23, the 1st Battalion, District of Columbia Militia, under the command of Major James McHenry Hollingsworth, was the first to cross into Virginia. At approximately 9:30 p.m., Company A, the “Anderson Rifles,” led by Captain Charles H. Rodier, crossed Chain Bridge and established a guard post. There, they captured two members of the Fairfax Cavalry—Sergeant John Thomas Ball and Private George F. Kirby—making them the first uniformed Confederate prisoners of war.

Shortly before midnight, Hollingsworth and the rest of the battalion crossed the aqueduct to secure the road and prevent the bridges from being burned. Meanwhile, Colonel Charles P. Stone led three District militia companies across Long Bridge, advancing as far as Four Mile Run to achieve the same objective.

The invasion began in earnest at 2 a.m. on Friday, May 24, 1861. Union troops crossed the Potomac River into northern Virginia, intent on securing Arlington Heights and Alexandria. The invasion force was divided into three columns. The right column crossed over Aqueduct Bridge, while the center and left columns crossed Long Bridge. The 11th New York “Fire Zouaves,” part of the left column, was transported by boat to Alexandria.

- Right Column: Led by Maj. Gen. Charles W. Sandford, New York Militia, and Capt. William H. Wood of the 3rd United States Infantry. 2nd United States Cavalry, Company B; 28th N.Y.S.M.; 5th N.Y.S.M.; 69th N.Y.S.M.; 14th N.Y.S.M. Engineers; President’s Mounted Guards (detachment).

- Center Column: Led by Col. Samuel P. Heintzelman, 17th U.S. Infantry. 2nd United States Cavalry, Company I; 12th N.Y.S.M.; 7th N.Y.S.M.; 25th N.Y.S.M.; 2nd New Jersey Infantry Regiment; 3rd New Jersey Infantry Regiment; 4th New Jersey Infantry Regiment; 3rd United States Artillery, Light Company E (1 section, 2 guns).

- Left Column: Led by Col. Orlando B. Willcox. 2nd United States Cavalry, Company E; President’s Mounted Guards (detachment); 1st Michigan Infantry Regiment; 3rd United States Artillery, Light Company E (1 section, 2 guns); 11th New York Infantry Regiment (Ellsworth Zouaves).

“As the regiment was crossing, all minds were full,” Col. Orlando B. Willcox of the 1st Michigan later reflected. “This was, for us, the actual beginning of the long, bitter story of the Civil War.”

From Aqueduct Bridge, the 28th and 5th New York State Militia (N.Y.S.M.) advanced about 1.5 miles toward the Leesburg and Alexandria Turnpike, while the 69th N.Y.S.M. remained near the bridge. As soon as the engineers arrived with shovels and pickaxes, they began constructing Fort Corcoran, named after their colonel. Meanwhile, Company B of the 2nd United States Cavalry, along with two companies from the 28th N.Y.S.M., advanced to the Loudoun & Hampshire Railroad. There, Lieutenant Charles H. Tompkins stopped a passenger train while accompanying U.S. Army engineers destroyed sections of track and burned two bridges over Four-Mile Run.

At that point, Major General Charles W. Sandford, commanding the First Division of the New York State Militia, arrived with his staff. He interviewed the passengers and examined their papers. With the exception of one sergeant from the Fairfax Rifles (part of Corse’s Battalion), whom he took prisoner, Sandford allowed the passengers to leave on the condition that they remain in the train until 5 p.m. He then proceeded to Arlington House, the home of Robert E. Lee. Lee’s wife, Mary Custis Lee, had left the estate in the care of her personal maid, Selina Norris Gray and family. To preserve the property and its family heirlooms—some of which had once belonged to George Washington—Sandford took Arlington House as his headquarters.

At Long Bridge, Colonel Samuel P. Heintzelman directed Company I of the 2nd United States Cavalry and the 25th N.Y.S.M. to turn right at the fork where the Columbia Turnpike and Alexandria Turnpike split. There, the New Jersey Brigade began constructing Camp Princeton, soon renamed Fort Runyon after their commander, Theodore Runyon. Heintzelman then ordered Captain S. W. Owen of the President’s Mounted Guards to lead the 12th N.Y.S.M. down the Alexandria Turnpike to Four-Mile Run near Roach’s Mills. From there, Captain Owen was to guide the 1st Michigan Infantry Regiment and a section of the 3rd United States Artillery, Light Company E, to the town of Alexandria, about 5.5 miles farther south.

As the sun rose, Commander Stephen C. Rowan, aboard the USS Pawnee, spotted three steamers carrying Colonel Elmer E. Ellsworth and his “Fire Zouaves” steadily approaching Alexandria. Concerned for the safety of women and children should a battle erupt, Rowan took it upon himself to send Lieutenant Reigart B. Lowry in a small boat to negotiate the town’s surrender.

In Alexandria, Confederate pickets had already warned of approaching Union troops, so the Virginia militia was not caught by surprise. Colonel George H. Terrett, commanding the Alexandria garrison, ordered his men to arm themselves and assemble. Amid the chaos, Lieutenant Lowry arrived under a flag of truce. He informed Terrett that an overwhelming Union force was about to enter the town and that “it would be madness to resist.” Terrett refused to surrender but requested several hours to evacuate. Lowry agreed and returned to the wharf, where a Virginia sentinel fired his musket before retreating.

At King Street Wharf, Lowry met Ellsworth, a former clerk from Abraham Lincoln’s law office in Springfield, Illinois, and relayed the terms of the truce.

“The commanding officer is already evacuating,” Lowry explained. “He promises to make no resistance. The town is full of women and children.”

“All right, sir, I will harm no one,” Ellsworth replied. The Zouaves proceeded to seize the port and telegraph office.

Terrett and his men boarded waiting train cars on the Orange & Alexandria Railroad to evacuate to Manassas Junction, leaving two cavalry companies behind to monitor enemy movements. Meanwhile, Captain Mottrom Dulany Ball and about 35 of his men were mounting their horses when Colonel Orlando B. Willcox arrived in town with his cavalry escort and accompanying artillery.

“Surrender, or I’ll blow you to hell!” Willcox demanded.

Ball protested that his men were still covered by the flag of truce and had time to evacuate, but Willcox—unaware of the agreement—dismissed the claim and took them into custody.

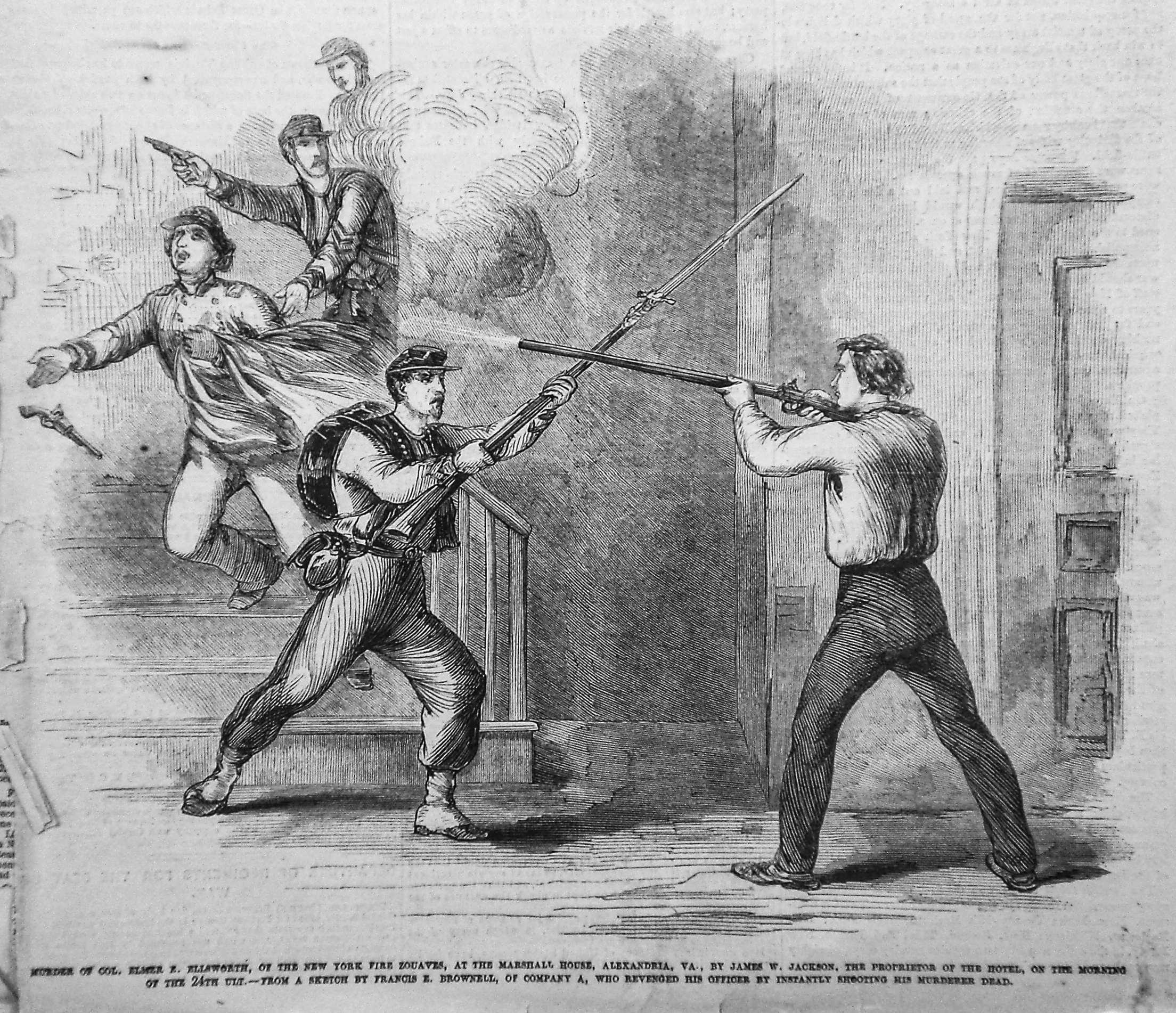

At the same time, Ellsworth and seven men headed for the Marshall House and its large Confederate flag. Determined to remove it, he and seven men rushed inside. As Ellsworth descended the stairs, flag in hand, James W. Jackson, the inn’s proprietor, suddenly appeared with a double-barreled shotgun and fired, killing Ellsworth instantly. In response, Corporal Francis Brownell, who had accompanied Ellsworth, shot and killed Jackson.

As Willcox was temporarily securing Ball’s men in the Alexandria slave pen, a soldier ran from the Marshall House to deliver the alarming news.

Willcox and Alexandria’s mayor, Lewis Mackenzie—old friends from Willcox’s time stationed at Fort Washington—met to discuss the situation. Mackenzie surrendered the town, and Willcox took control of the offices of the Alexandria Gazette. There were no reprisals. The 1st Michigan and 11th New York regiments established camp on Shuter’s Hill, just west of town, where they began constructing Fort Ellsworth in honor of the fallen colonel.

The Union invasion of northern Virginia had begun at the cost of one officer, but the impact was deeply felt at the White House. President Lincoln gave Ellsworth a hero’s funeral, and though the North mourned the loss of a promising young leader, their early success fueled hopes that the war would end quickly.

Sources

Annual Report of the Adjutant General of the State of New York. Albany: C. Van Benthuysen, 1862.

Brooklyn Daily Eagle (Brooklyn, NY) 29 May 1861.

Daily National Intelligencer (Washington, DC) 25 May 1861.

Evening Star (Washington, DC) 24 May 1861.

Goodheart, Adam. 1861: The Civil War Awakening. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2011.

Johnson, William Page, II. “Colonel Mottrom Dulany Ball.” The Fare Facs Gazette. Fairfax: Historic Fairfax, Inc., Summer 2015.

Leepson, Marc. “The First Union Civil War Martyr: Elmer Ellsworth, Alexandria, and the American Flag.” The Alexandria Chronicle. Alexandria: Alexandria Historical Society, Fall 2011.

Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion. Series I, Vol. 4. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1896.

Pulliam, Ted. “The Civil War Comes to Duke Street.” The Alexandria Chronicle. Alexandria: Alexandria Historical Society, Fall 2011.

Scott, Robert Garth, ed. Forgotten Valor: The Memoirs, Journals, & Civil War Letters of Orlando B. Willcox. Kent: Kent State University Press, 1999.

The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Series I, Vol. II. With additions and corrections. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1902.

Wallace, Lee A., Jr. 17th Virginia Infantry. Lynchburg: H.E. Howard, Inc., 1990.

5 thoughts on “Crossing into Conflict: The Union’s First Movements into Virginia in 1861”