In 1861, Trans-Allegheny Virginia was a landscape of hills and mountains cut by rivers like the Kanawha, Little Kanawha, Tygart, Cheat, and Greenbrier. The region consisted largely of small towns and subsistence farms, with limited industry beyond coal mining, salt works, and a nascent iron trade. The first oil wells were drilled on the eve of the Civil War. Compared with eastern Virginia, slavery was uncommon and played only a marginal role in the local economy.

Because the region lacked a strong network of improved roads and railroads, the Ohio River served as its principal artery, running 277 miles along Virginia’s western border. Wheeling, then Virginia’s fourth-largest city, rose in the Northern Panhandle between Ohio and Pennsylvania, benefiting from immigration and industrial investment flowing from both states. The coming of war threatened to constrict this profitable trade with wealthier neighbors.

These factors left much of the population unsympathetic to secession. Rather than leave the Union, a movement gathered to sever ties with eastern Virginia and form a new state, realized as West Virginia in 1863. In June 1861, Unionists in the northwest formed a “Reorganized State of Virginia,” based in Wheeling, with Francis H. Pierpont as its governor. A significant minority still favored secession, however, and guerrilla warfare, raids, and civil unrest plagued the region throughout the conflict.

In late April 1861, Ohio Governor William Dennison recruited George B. McClellan to command the state’s volunteers. On May 3, General Orders No. 14 created the Department of the Ohio, combining Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio into a single military district. Recalled to federal service at age thirty-four, McClellan was promoted to major general and given command of the district. He would organize the invasion and occupation of western Virginia that summer.

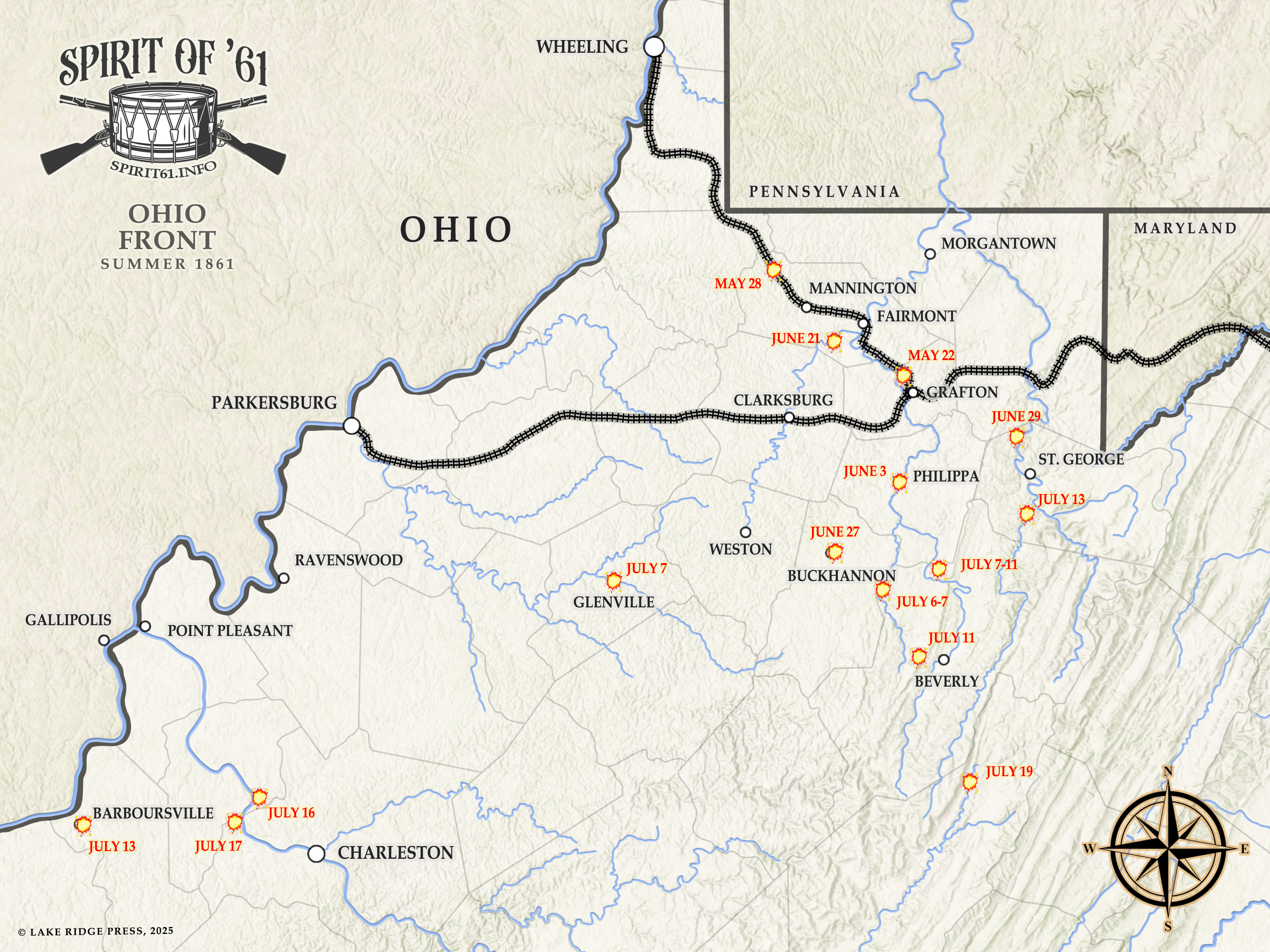

The Ohio Front can be subdivided into two regions: the Tygart and Cheat River valleys and the Kanawha Valley. As along the Potomac, results hinged on coordination across these subregions. Here, the pattern reversed. Union commanders coordinated effectively, keeping Confederate forces split, while dysfunction within Confederate commands produced both military and political setbacks.

Tygart and Cheat River Valleys

A border compromise in the 1780s left Virginia with a 63-mile ribbon of land thrust between Ohio and Pennsylvania, the Ohio River marking its western boundary. In this Northern Panhandle, the city of Wheeling was geographically and culturally closer to Pittsburgh than to Richmond, with burgeoning industry and a large German immigrant population. Farther south, the Baltimore & Ohio and the Northwestern Virginia railroads, the only rail lines crossing western Virginia, converged at Grafton on the Tygart Valley River.

This was a strategic but difficult region to defend. To secure it, Robert E. Lee called on Maj. Alonzo Loring in Wheeling and Francis M. Boykin Jr. of Weston to raise volunteer companies to protect the vital railroads. He ordered Col. George A. Porterfield, a Mexican War veteran, to proceed to Grafton and organize the volunteers assembling there. Recruits proved scarce, and the few hundred who appeared were poorly armed and equipped.

Politically, northwestern Virginia was strongly unionist. Citizens counter-mobilized, raising companies for Federal service. U.S. Congressman John S. Carlile and other unionist delegates to the Richmond Secession Convention convened their own meeting in Wheeling to debate how to respond to secession. Meanwhile, the 1st Virginia Regiment (U.S.), led by Colonel Benjamin Franklin Kelley, organized at Camp Carlile on Wheeling Island.

After the secession vote, Porterfield ordered bridges on the Baltimore & Ohio and Northwestern Virginia railroads north and west of Grafton destroyed. McClellan responded by dispatching Brig. Gen. Thomas A. Morris with the 1st Virginia (U.S.) and regiments from Indiana and Ohio to secure the line. They defeated Porterfield at Philippi on June 3, 1861.

As reinforcements arrived, Robert E. Lee’s adjutant general, Robert S. Garnett, was promoted to brigadier general and given command of Confederate forces in northwestern Virginia. He fortified positions at Laurel Hill and Rich Mountain to guard the two principal mountain roads into the Shenandoah Valley. Garnett appealed to Henry A. Wise, then operating in the Kanawha Valley, to unite their forces against McClellan, but Wise hesitated to cooperate.

In late June, McClellan joined his army and organized an offensive against Garnett. Coordinating with Brig. Gen. Jacob D. Cox’s advance in the Kanawha, his forces turned Garnett out of his mountain positions. By mid-July, Garnett was dead and his command scattered, with hundreds taken prisoner. On July 16, the 14th Indiana occupied Cheat Mountain, placing northwestern Virginia firmly in Union hands. With only brief interruptions, it remained so for the rest of the war.

Kanawha River Valley

The Kanawha River runs 97 miles from the confluence of the New and Gauley rivers to the Ohio. In 1861, the valley’s largest town was Charleston, population 1,520. South of town, the Dickinson saltworks produced large quantities of salt, which was critical for preserving food and curing leather. The river itself offered a navigable artery into the heart of western Virginia.

On May 3, 1861, Governor John Letcher commissioned Charleston businessman Christopher Q. Tompkins as a colonel and authorized him to raise a regiment in the Kanawha. Lieutenant Colonel John McCausland, a Virginia Military Institute professor, was sent to help muster and train the units. Complicating matters, former Governor Henry A. Wise, a Tidewater planter, received a Confederate commission with authority to raise his own force to defend the Kanawha Valley, bypassing state authorities.

Wise, an energetic secessionist, used his political connections to raise several combined-arms regiments for his “Wise Legion,” surrounding himself with veteran staff officers to offset his lack of military experience. He established his headquarters at Charleston on June 26 and immediately employed military force to suppress the area’s strong unionist sentiment. The heavy-handed approach worked at first but bred deep resentment.

To counter Confederate influence in the Kanawha Valley, Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan turned to Brig. Gen. Jacob D. Cox, an Ohio attorney and state senator. After Virginia’s secession vote, local unionists had assured McClellan they could keep events in hand. But he could not allow Wise to operate unchecked while he moved against Brig. Gen. Robert S. Garnett’s army to the north.

Cox advanced deliberately up the Kanawha River, skirmishing at several points but suffering a sharp defeat at Scary Creek. Meanwhile, McClellan’s operations in the Tygart and Cheat valleys shattered Garnett’s army. Fearing encirclement by Union columns moving down from the north, Wise evacuated Charleston on July 24 and fell back to Gauley Bridge, narrowly escaping a trap. Cox’s brigade entered Charleston on the 26th and Gauley Bridge on the 29th, clearing the Kanawha Valley of Confederate forces for the time being.

Sources

Benham, Henry Washington. Recollections of West Virginia Campaign with ‘The Three Months Troops’. Boston: Privately Printed, 1873.

Boeche, Thomas L. “McClellan’s First Campaign” in America’s Civil War (January 1998): 30-36.

Cox, Jacob Dolson. Military Reminiscences of the Civil War. Vol. I. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1900.

Hall, Granville Davisson. The Rending of Virginia, A History. Chicago: Mayer & Miller, 1902.

Haselberger, Fritz. Yanks from the South! The First Land Campaign of the Civil War. Baltimore: Past Glories, 1987.

Hardway, Ronald V. On Our Own Soil: William Lowther Jackson and the Civil War in West Virginia’s Mountains. Charleston: Quarrier Press, 2003.

Lowry, Terry D. The Battle of Scary Creek: Military Operations in the Kanawha Valley April – July 1861. Charleston: Quarrier Press, 1982, 1998.

Phillips, David L. War Diaries: The 1861 Kanawha Valley Campaigns. Leesburg: Gauley Mount Press, 1990.

Rice, Otis K. and Stephen W. Brown. West Virginia: A History. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1993.

Stutler, Boyd B. West Virginia in the Civil War. Charleston: Education Foundation, Inc., 1966.