During the American Civil War, Virginians found themselves divided not only by ideology and geography, but by government itself. From 1861 to 1864, two men, John Letcher and Francis Pierpont, each claimed to be the legitimate governor of Virginia. One led the Confederate state government from Richmond, while the other presided over the Unionist Reorganized Government from Wheeling and later Alexandria. Their rival claims reflected the fractured loyalties of a state torn between secession and union, and their dueling administrations offer a striking example of how legitimacy in wartime is often as much a matter of practical governance as of law.

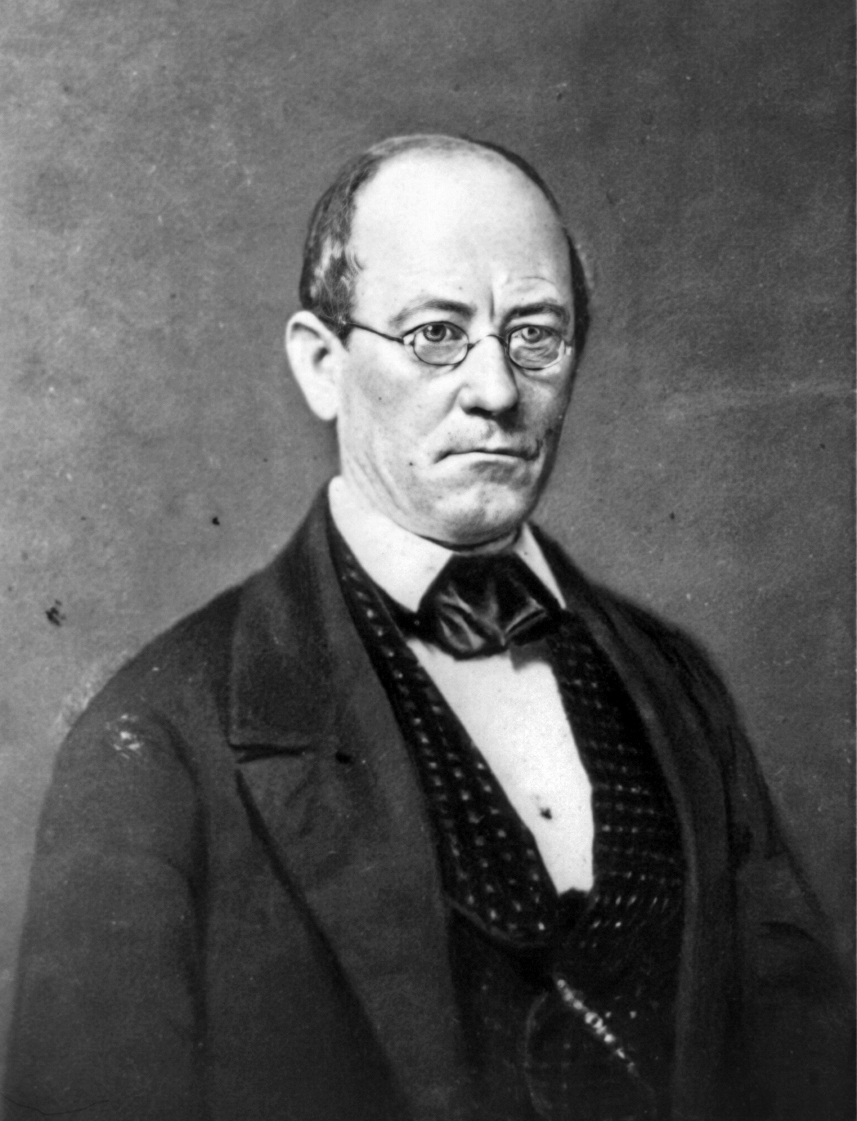

John Letcher (1813–1884)

John Letcher was born into a middle-class family in Lexington, Virginia, where his parents worked as shopkeepers and held modest aspirations for their son. His father hoped he would become a carpenter, but Letcher had little interest in manual labor. He attended Washington College for a year before turning to politics. He later became editor of the Lexington Valley Star and passed the bar to establish a private law practice.

Nicknamed “Honest John,” Letcher held moderate views on many of the contentious issues of his time. Though not a fire-eating secessionist, he believed Virginia had the right to leave the federal union if a majority of its citizens voted to do so. He advocated reforms to bridge the political and economic divide between eastern and western Virginia and, for a time, supported the gradual emancipation of slaves as a practical step toward that end.

He was elected to the U.S. Congress in 1851 and ran for governor of Virginia in 1859. Support from western Virginians helped secure his victory, and he assumed office on January 1, 1860. Although he publicly expressed hope that the growing sectional crisis could be resolved peacefully and supported Northern Democrat Stephen A. Douglas in the 1860 presidential election, he nonetheless took steps to prepare the state for the possibility of war.

In early 1861, Letcher helped organize a peace conference in Washington, D.C., which ultimately failed to defuse the growing conflict. Like many conditional Unionists, he was outraged by President Abraham Lincoln’s call for 75,000 volunteers to “suppress the rebellion” in the Deep South. In response, the bespectacled governor replied defiantly, declaring that Lincoln had “chosen to inaugurate civil war.”

After the Richmond Secession Convention voted to withdraw from the Union, a decision ratified by a majority of white male voters on May 23, 1861, Letcher mobilized the state militia and helped enlist prominent figures such as Robert E. Lee and Thomas J. Jackson to the Confederate cause. He served as Virginia’s wartime governor until January 1, 1864, when he was succeeded by William “Extra Billy” Smith.

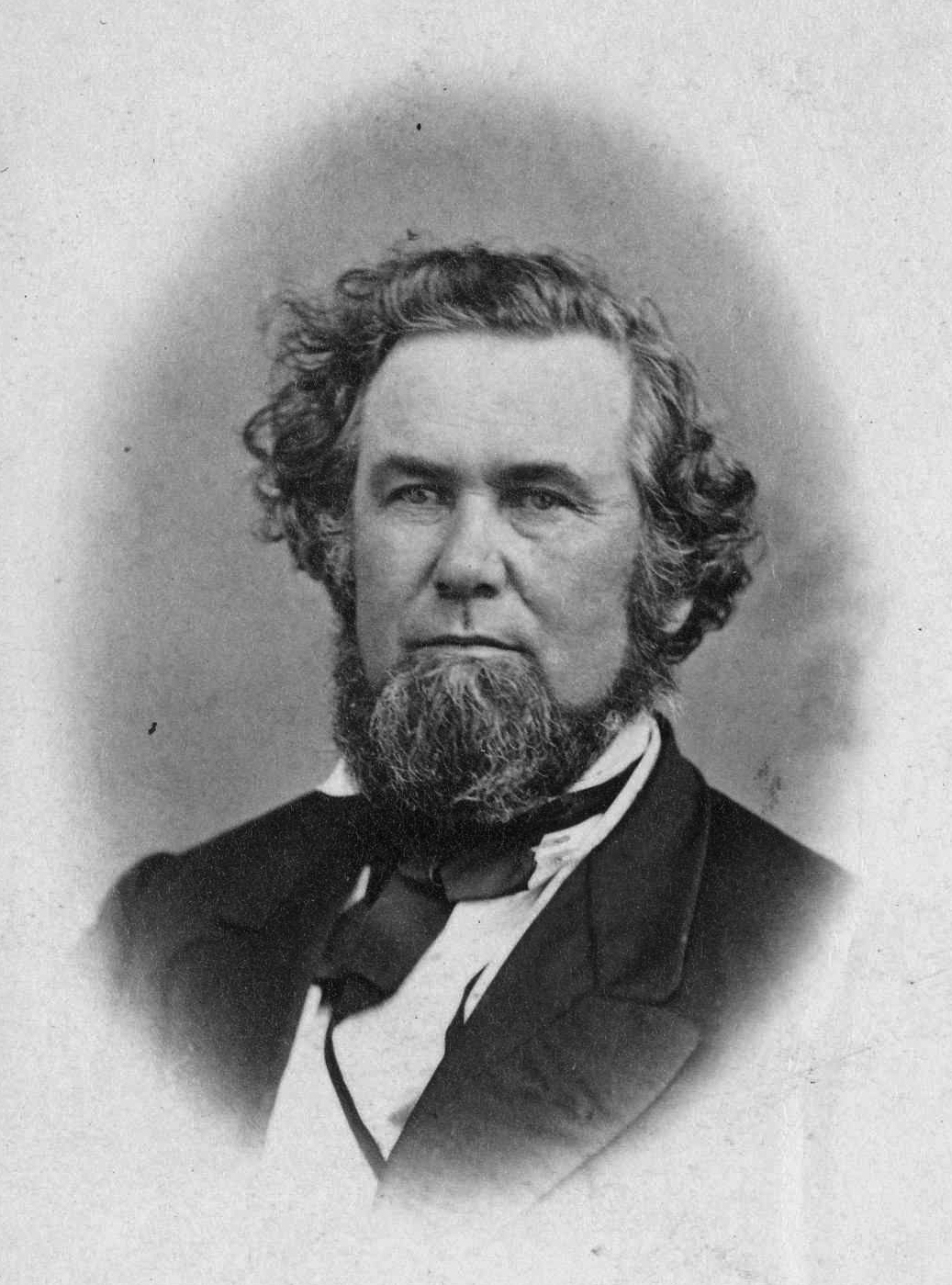

Francis H. Pierpont (1814-1899)

Like Letcher, Francis Harrison Pierpont (also spelled Peirpoint) was a lawyer from a middle-class background. He grew up in what is now Monongalia County, West Virginia, near the Pennsylvania border, where his parents operated a leatherworking business. Pierpont graduated from Allegheny College in Meadville, Pennsylvania, and went on to work as a schoolteacher and as an attorney for the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. He was a supporter of the Whig Party until its collapse.

Pierpont’s wife, Julia Augusta Robertson, was a committed abolitionist. After witnessing the brutal treatment of slaves during a visit to Mississippi as a young man, Pierpont’s antislavery convictions were firmly cemented. He strongly opposed secession, and when the Richmond Secession Convention voted to leave the Union, he joined other prominent Unionists from western Virginia in organizing a rival convention in the city of Wheeling.

On June 20, 1861, Francis Pierpont was unanimously elected governor of the Reorganized State of Virginia, a Unionist rump state that exercised authority over areas under Union military control. Its leaders argued that Governor John Letcher and other state officials had forfeited their offices by embracing secession. President Abraham Lincoln agreed and recognized the legitimacy of the new government.

After West Virginia was admitted to the Union in 1863, Pierpont relocated his government from Wheeling to Alexandria, Virginia. Following the fall of the Confederacy, he moved to Richmond and undertook the difficult work of Reconstruction. Just a few years later, however, Pierpont was unceremoniously removed from office on April 4, 1868, after Congress placed Virginia under military rule. Disillusioned, he returned to West Virginia, where he spent the remainder of his life.

A Tale of Two Governments

The existence of two competing governments, each claiming legitimate authority over the same territory, is not uncommon in times of war. Such disputes are often settled on the battlefield, and from June 1861 to May 1865, the question of who was a Virginian’s rightful governor largely depended on which side of the front lines they lived.

Letcher’s claim to legitimacy rested on the will of the electorate and, ultimately, on the legality of secession. He argued that the decision to secede had been made by an elected convention of delegates from across the state and ratified by an overwhelming majority of voters in the May 23, 1861, referendum. “You [referring to Unionists in western Virginia], as well as the rest of the State, have cast your vote fairly, and the majority is against you,” he wrote. “It is the duty of good citizens to yield to the will of the State.”

Article 14 of the Virginia Declaration of Rights, adopted on June 12, 1776, affirms that the people are entitled to a unified government: “No government separate from, or independent of, the government of Virginia, ought to be erected or established within the limits thereof.”

Not only had a majority of Virginians voted in favor of secession, but most of the state’s elected officials also accepted it as a legal and political reality. Three of Virginia’s living former governors became Confederate generals, and former U.S. President John Tyler, who had served as the state’s 23rd governor from 1825 to 1827, was elected to the Confederate Congress. The General Assembly, with the exception of a few members who resigned, remained intact and continued to conduct business at the Capitol in Richmond.

Francis Pierpont, U.S. Congressman (and later Senator) John S. Carlile, and other Virginia Unionists viewed secession as unconstitutional. As a result, they considered the actions of the Virginia Secession Convention and the subsequent referendum to be null and void. On June 17, 1861, the Wheeling Convention adopted A Declaration of the People of Virginia, which proclaimed: “All acts of the said [secession] convention and executive tending to separate this Commonwealth from the United States, or to levy and carry on war against them, are without authority and void; and the offices of all who adhere to the said convention and executive, whether legislative, executive, or judicial, are vacated.”

President Abraham Lincoln accepted the actions of the Wheeling Convention, and two U.S. Senators along with four (later five) Representatives from the Reorganized Government of Virginia were seated in Congress, less than one-third of the state’s full House delegation.

On May 9, 1865, one month after General Robert E. Lee’s surrender to General Ulysses S. Grant, President Andrew Johnson issued an executive order “To Reestablish the Authority of the United States and Execute the Laws Within the Geographical Limits Known as the State of Virginia.” This order paved the way for Pierpont’s government, with federal support, to assume control over the entire state. It read, in part:

“That all acts and proceedings of the political, military, and civil organizations which have been in a state of insurrection and rebellion within the State of Virginia against the authority and laws of the United States, and of which Jefferson Davis, John Letcher, and William Smith were late the respective chiefs, are declared null and void. All persons who shall exercise, claim, pretend, or attempt to exercise any political, military, or civil power, authority, jurisdiction, or right by, through, or under Jefferson Davis, late of the city of Richmond, and his confederates, or under John Letcher or William Smith and their confederates, or under any pretended political, military, or civil commission or authority issued by them or either of them since the 17th day of April, 1861, shall be deemed and taken as in rebellion against the United States, and shall be dealt with accordingly.”

President Andrew Johnson, May 09, 1865

The order retroactively nullified any actions taken by John Letcher or his successor, William Smith, dating back to April 17, 1861. It justified this by asserting that, having engaged in rebellion against the United States, they had forfeited their legitimacy and were no longer lawfully exercising civil authority. In the eyes of the federal government, therefore, Virginia had no legitimate government between April 17 and the establishment of the Reorganized Government in Wheeling on June 20, 1861.

John Letcher and Francis Pierpont represented two irreconcilable visions of Virginia’s future during the Civil War. Letcher, a moderate turned secessionist, believed the sovereignty of the state included the right to leave the Union if its citizens so chose. He saw the May 1861 referendum as a legitimate expression of the popular will and viewed the Confederate government in Richmond as the rightful authority. Pierpont, by contrast, held that secession was not only unconstitutional but void of legal force, and that loyalty to the United States superseded any state referendum. Where Letcher appealed to the traditional principles of state sovereignty and majority rule, Pierpont grounded his authority in fidelity to the Union and the continuity of the U.S. Constitution.

Though both men acted with conviction and claimed legal legitimacy, the weight of history ultimately favored Pierpont’s position. With the defeat of the Confederacy and the federal government’s backing, the Reorganized Government was recognized as the lawful government of Virginia. Pierpont’s administration, though limited in its wartime reach, laid the groundwork for the restoration of civil authority in the aftermath of the war. His argument that rebellion stripped officials of lawful power was affirmed by executive action and Congressional acceptance.

In the end, the question of legitimacy was settled not by constitutional debate but by the outcome of war. Letcher’s vision dissolved with the Confederacy, while Pierpont’s survived (however briefly) as the bridge between wartime loyalty and postwar reconstruction. Their contrasting legacies reflect the deep divisions of their time, but also the enduring tension between state and national authority that the war, for a time, resolved in favor of union.

Sources

Ambler, Charles H. Francis H. Pierpont: Union War Governor and Father of West Virginia. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 1937.

Boney, F.N. John Letcher of Virginia: The Story of Virginia’s Civil War Governor. University, AL: University of Alabama Press, 1966.

Hall, Granville D. The Rending of Virginia: A History. Chicago, IL: Mayer & Miller, 1902.

Snell, Mark A. West Virginia and the Civil War. Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2011.