In the early days of the Civil War, as Virginia seceded and Confederate forces rushed to secure key positions across the state, Jamestown Island—better known as the birthplace of English America—was drawn into the conflict.

Between April and July 1861, the Confederacy quickly turned Jamestown Island’s strategic position on the James River into a forward defensive outpost. The result was Fort Pocahontas, a short-lived but important battery and troop station that only recently emerged from the shadows of history through archaeology and rediscovery.

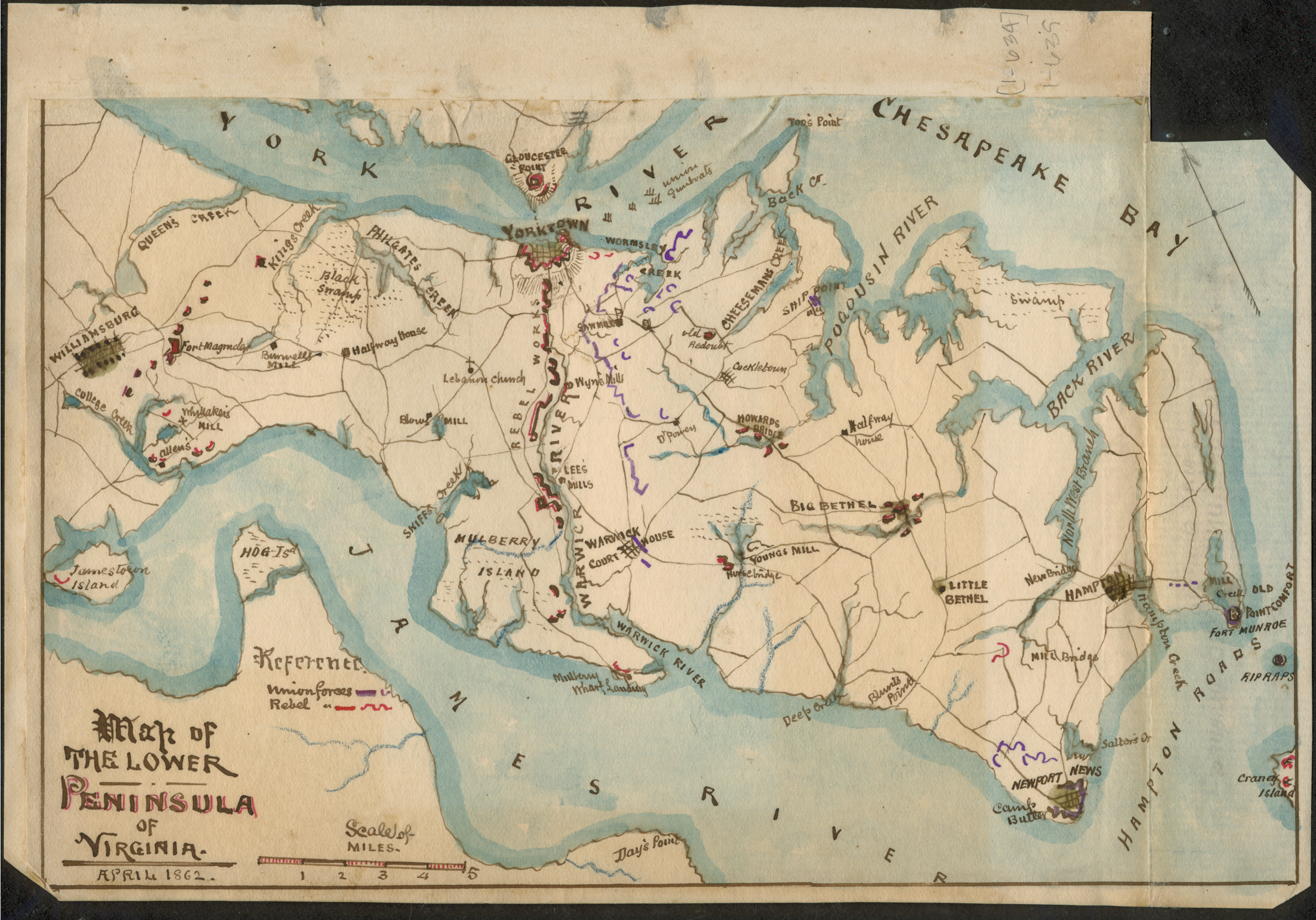

By 1861, Jamestown Island’s colonial prominence had long since faded. Still, its location on the James River made it an ideal site for controlling naval access to Richmond and defending against Union incursions from the Chesapeake Bay. At its narrowest point, the river stretched about a mile across from the island to Swan’s Point on the western shore.

William Griffin (Orgain) Allen, one of Virginia’s wealthiest citizens and a staunch secessionist, owned all of Jamestown Island along with several other properties across the state. At the outbreak of war, he raised an artillery unit known as the Brandon Artillery at his own expense. Using both slave and paid labor, Allen began constructing a fort at the island’s eastern tip, in the shadow of the ruined 1680 church tower.

Letters and orders from Confederate headquarters in Richmond during May and June 1861 reveal the urgency with which Jamestown Island was militarized. On May 7, Major John M. Patton was ordered to take command of volunteer troops assigned to the island, while Captain Harrison F. Cocke of the Virginia Navy was placed in charge of constructing the battery there and at Fort Powhatan farther upriver. Two companies were already en route: 85 men of the Greensville Guard, led by Captain William Henry Briggs, and Captain George M. Waddill’s company from Charles City County.

By May 28, additional special orders assigned Captain Tyler C. Jordan’s Bedford Light Artillery to Jamestown and directed Colonel James G. Hodges’ 14th Virginia Infantry Regiment to serve as a protective force for the new installation. The objective was to establish a defensive line along the James River to guard against Union gunboats and support larger coastal batteries. At the time, an estimated 15 companies—totaling around 1,050 men—were stationed on the island, in addition to two 9-inch guns and six 32-pounders.

A letter dated June 2, 1861, reported that eight more field guns—including 6- and 12-pounders—were being sent to Jamestown. The guns were to be immediately transported to the neck of the island and positioned under the supervision of Lieutenant Colonel Benjamin S. Ewell, president of the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg. Many local men, previously employed in the wood trade, were available to assist as laborers in building the fortifications. Overall command of the battery was given to Captain Catesby ap Roger Jones, a former U.S. Navy officer.

Fort Pocahontas covered roughly an acre and was fortified with a six-foot-high earthen embankment and a ditch measuring 15 feet wide and eight feet deep. Its most prominent feature was a 158-foot-long gun platform supported by nearly 100 joists and fastened with close to 1,000 iron spikes, accessed by a ramp.

It had three powder magazines, including one circular, brick-lined chamber and another large “bombproof” structure with air shafts. Additional construction included a robust wharf built by the Brandon Artillery, using 144 pilings and over 30,000 board feet of timber.

On July 4, 1861, Virginia’s first Independence Day after secession, the Confederate garrison on Jamestown Island marked the occasion with celebration and ceremony. The day was filled with speeches, dancing, food, and sailing, joined by dozens of local women and even former U.S. President John Tyler.

At 71, Tyler delivered a fiery speech, declaring that if a fight came, “although he was a man of the olden time, he would shoulder his musket and take his place in the ranks.” The men, filled with the optimism of green soldiers, responded with “vociferous applause.”

Though it never saw a major battle, Fort Pocahontas played a key role in the Confederacy’s early war strategy. Positioned on the James River, it served as a defensive outpost to deter or delay Union naval advances toward Richmond. The fort also functioned as a training and muster site for new Confederate recruits and was reportedly used to test the iron plating later installed on the CSS Virginia, the Confederacy’s first ironclad warship.

However, the fort’s military importance was short-lived. By mid-1862, as Union forces under General George B. McClellan advanced up the Peninsula, the Confederates withdrew from forward positions like Fort Pocahontas to reinforce deeper defensive lines. Over time, it faded from memory. Jamestown’s colonial legacy overshadowed its Civil War chapter, and the remains of Fort Pocahontas were slowly buried beneath layers of sediment, vegetation, and neglect.

In the early 2000s, archaeologists at Historic Jamestowne began uncovering clear evidence of the Confederate occupation. They identified trenches, earthen embankments, and artillery platforms as components of the 1861 fortifications. Drawing on military records and the layout of the structures, aligned with mid-19th-century artillery doctrine, they formally identified the site’s boundaries.

Excavations uncovered more than just fortifications—they revealed artifacts like ammunition, military buttons, and tools that directly linked the site to the Confederate troops stationed there in 1861. This rediscovery expanded Jamestown’s story, showing that the island was not only the birthplace of English America but also a military post during one of the nation’s most pivotal conflicts.

Today, Fort Pocahontas exists not as a reconstructed site, but as a preserved archaeological feature. Interpretive signage and ongoing research by the National Park Service and Historic Jamestowne help visitors understand the Civil War chapter layered into this historic landscape.

Sources

Crews, Edward R. and Timothy A. Parrish. 14th Virginia Infantry. Lynchburg: H.E. Howard, Inc., 1995.

Gregory, G. Howard. 53rd Virginia Infantry and 5th Battalion Virginia Infantry. Lynchburg: H.E. Howard, Inc., 1999.

Koleszar, Marilyn Brewer. Ashland, Bedford, and Taylor Virginia Light Artillery. Lynchburg: H.E. Howard, Inc., 1994.

Richmond Dispatch (Richmond, VA) 5 June 1861.

Riggs, David F. Embattled shrine: Jamestown in the Civil War. Shippensburg, PA: White Mane Pub. Co., 1997.

Staunton Spectator (Staunton, VA) 2 July 1861.

Staunton Spectator (Staunton, VA) 9 July 1861.

The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Series I, Vol. II. With additions and corrections. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1902.

The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Series I, Vol. LI, Part II. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1897.

Weaver, Jeffrey C. 10th and 19th Battalions of Heavy Artillery. Lynchburg: H.E. Howard, Inc., 1996.

One thought on “Fort Pocahontas: Jamestown Island’s Forgotten Confederate Stronghold”