Occurring on Friday, July 5, 1861, the Skirmish at Smith’s Farm was significant because Louisianan Lt. Col. Charles Dreux became the first field grade Confederate officer killed during the Civil War. Yet few people, even Civil War historians, have ever heard of it. Sometimes inaccurately called Young’s Mill, I refer to it as Smith’s Farm to distinguish it from another skirmish that took place the following week nearby along Cedar Lane. Young’s Mill was where the Confederates were camped, not where the skirmish took place.

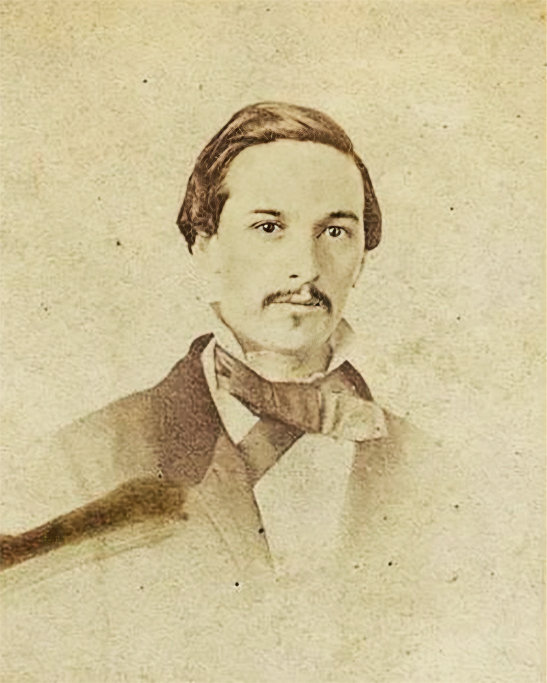

Charles Didier Dreux (1832-1861) was a Louisiana Creole descended from a French aristocratic family. He was captain of the Orleans Cadets, helped form the 1st Louisiana Infantry Battalion shortly after the firing on Fort Sumter, and was elected its lieutenant colonel. His death was much mourned throughout the South, but he became the subject of controversy a few years ago when vandals repeatedly defaced and stole a monument to him in New Orleans.

Part of the reason for this skirmish’s obscurity is that half the story is missing. A full account of Dreux’s death, from multiple Confederate perspectives, appears in The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Series I, Vol. II under the subheading July 5, 1861–Skirmish near Newport News, Va. There are no accompanying Union reports of the skirmish. A Civil War Trails sign at the site doesn’t mention which unit represented the Union side at all.

Among the few books that mention this skirmish was Lee’s Tigers: the Louisiana Infantry in the Army of Northern Virginia by Terry L. Jones, published in 1987. It was also silent about what Union troops nearly fell into Dreux’s ambush.

A Union report of this skirmish does appear in The War of the Rebellion, Series I, Vol. II, but because it was written over a week later (July 15, 1861), it didn’t end up in the same section as the others. On page 741, Maj. Gen. Benjamin F. Butler briefly mentions the skirmish but misspells Dreux’s name:

“I have further the honor to report that in a skirmish between Newport News and Warwick, by a patrolling party numbering twenty-five, of Colonel Hawkins’ regiment, under command of Captain Hammell, and a detachment of Louisiana volunteers, numbering one hundred and fifty, under the command of Colonel De Russy, late of the U.S. Army, Colonel De Russy and one other officer of the rank of captain, name unknown, were killed, and seven men wounded. No one was injured upon our side.”

As I was researching something else, I accidentally came across a detailed account of the skirmish from the Union perspective reprinted in the Lafayette, Indiana Weekly Courier. I thought I had discovered a totally new skirmish, but since it sounded vaguely familiar, and involved the death of a Confederate officer, I dug further. The Union commander mentioned was named Hammell, of Hawkins’ New York Zouaves. Rush C. Hawkins was colonel of the 9th New York Infantry Regiment, recruited primarily from New York City. Company F was commanded by Capt. William W. Hammell.

The book The Ninth Regiment, New York Volunteers (Hawkins’ Zouaves), published in 1900, does mention the skirmish, and also says that “the enemy lost in the affair a Colonel Dreux, of Louisiana, and one captain killed.” However, both sources say this skirmish happened on Thursday, July 4th, while Dreux was actually killed on the 5th.

I believe, because of the discrepancy in dates and Butler’s misspelling of Dreux’s name, historians have not connected all of these accounts together. The following is a transcription of the article from the Weekly Courier:

A Bloody Skirmish Near Ft. Monroe.

The Fort Monroe correspondent of the Philadelphia Inquirer thus describes a bloody skirmish which took place in that vicinity last Thursday week, between a party of Hawkins’s New York Zouaves, numbering twenty five men and a company of rebels:

The expedition had advanced about two miles further when they were surprised to discover an armed force of rebels lying in the bushes by the road side on their flank and side. They believed it an ambuscade into which they had been drawn, and expected in an instant to be mowed down by their lurking enemy. Capt. Hammel, at this juncture, with the most commendable coolness, ordered his men to break ranks, each pick his man, fire, and then retreating to the woods on the other side of the road, each man, if possible, get behind a tree.

A moment more and they poured a volley into the bushes. The shot was promptly returned and a brisk engagement was progressing, when an officer, apparently a Colonel, accompanied by an officer of superior rank, sprang out into the road exclaiming at the top of his voice—Stop, stop for God’s sake stop—you’re shooting your own men! Don’t you remember the squad that went out last night with Captain—’WASHINGTON!’ ‘WASHINGTON!’ ‘WASHINGTON!’ was undoubtedly the rebel watchword. The officers and their men wore uniforms almost precisely like the First Vermont regiment, and for a moment Captain Hammel looked upon them with the thought that he had been firing upon members of that regiment who were out upon an expedition unknown to him. The next moment however, he discovered the white secession flag upon their hats and ordered his men to fire.

There were three Minie rifles in the company, and two of these—one in the hands of Sergeant Martin—were aimed at the two officers. Both were shot fatally. The ball from Martin’s rifle entered the left side of the rebel Colonel. He placed both hands upon the wound and fell. The other officer appeared to have been hit in the head or neck. He also fell, dropping the musket in his hand.

A number of soldiers immediately thereupon rushed from the bushes, and seizing the bodies and the guns, dragged them in after them, the ground and bushes being deeply dyed with blood on the spot. The firing then continued briskly on both sides for several minutes, when the rebels, hastily gathering up their dead and wounded, fled in great confusion up the road. At this instant, and just as Captain Hammel and his men had formed to pursue the party who just loaded their pieces, he was surprised to see a body of about eighty dragoons, with a field piece, sweeping down toward them. The retreating infantry poured forth to meet the approaching cavalry for support. Capt. Hammel’s men reserved their fire and still pursued. A moment after the rebel infantry and cavalry came into collision, and a most terrible confusion ensued. Captain H. then ordered his men to fire, and they sent twenty-five balls whistling into the mingled mass of horses and men. Shrieks, and groans, and yells, and imprecations filled the air. A portion of the horses wheeled about, and two or three of them staggered and almost fell. A scene of the most indescribable confusion resulted. Horses trampled upon the infantry, and after one or two fruitless attempts to rally, the whole force fled. From the disparity of the numbers of the rebel and Federal forces, it was not thought prudent by Capt. Hammel to pursue the retreat.

Unfortunately, I don’t have access to a digital archive of the Philadelphia Inquirer, so I was unable to look at the original article. Oftentimes other newspapers published abridged versions of dispatches, so this account may be missing details that appear in the original. But this information goes a long way toward filling in the blanks and helping to tell the full story of this obscure but impactful event.