If you search for any mention of a Civil War skirmish in Buckhannon, West Virginia in 1861 in the usual sources, you won’t find it. In fact, any information about Buckhannon prior to George McClellan’s occupation on June 30-July 1st is in short supply. There are a few references to a brief Confederate expedition to Buckhannon, but again, without many details.

That’s why I was surprised to read an account of a skirmish in Buckhannon in June 1861 in William Bernard Cutright’s History of Upshur County, West Virginia (1907), a story repeated by historian Fritz Heselberger in Yanks from the South! (1987). It speaks of the brave defense of Buckhannon by unionist home guard against a rebel incursion led by someone named “Col. Turk”. This colorful tale undoubtedly contains a grain of truth, but how much?

As Virginia’s secession appeared all but certain in the spring of 1861, Virginia Provisional Army commander Robert E. Lee sent Col. George A. Porterfield to what was then Northwest Virginia to organize the state militia. Popular sentiment in the region was decidedly pro-Union, however, and recruits were hard to find. Lack of basic supplies, uniforms, and weapons compounded his problem. He only gathered a few hundred poorly trained men.

Towards the end of May, Porterfield sent Lt. Col. Jonathan McGee Heck (1831-1894), an attorney from Marion County, (West) Virginia, to Richmond to explain, in person, the dire situation they faced. Heck was in Staunton gathering reinforcements and supplies during the Philippi disaster. When Heck returned to the Northwest, Confederate forces had a new commander in the form of Brig. Gen. Robert S. Garnett. Garnett placed Heck in command of the 25th Virginia Infantry Regiment and ordered him to fortify Rich Mountain.

Supplying an army in the Allegheny Mountains was a logistical nightmare. The Confederate supply line stretched 100 miles from Staunton to Beverly. That was roughly a week’s journey over the mountains by wagon. Heck wrote that it took him and his reinforcements, including an artillery battery, from June 7 to June 15 to reach Huttonsville from Staunton, and Beverly was another 11.5 miles north of Huttonsville. Since “an army marches on its stomach”, the Confederates resorted to foraging to fill in the gaps.

So, in late June, Lt. Col. Heck took his men and wagons and marched toward Buckhannon, looking for supplies. Buckhannon, population 427 in 1860, is the seat of Upshur County. It is located along the Buckhannon River and Staunton-Parkersburg Turnpike. The Turnpike was a vital transportation route from the Shenandoah Valley to the Ohio River. Buckhannon, approximately 23 miles east of the Confederate camp on Rich Mountain, became a kind of no man’s land between Confederate forces and Union forces camped at Philippi and Clarksburg.

In his regimental history of the 25th Virginia, Richard L. Armstrong, wrote:

“On June 26 Colonel Heck and about 300 men of the 25th Infantry left Camp Garnett (as the camp on Rich Mountain was now being called) and marched for Buckhannon. Colonel Heck and his command occupied the count[y] seat of Upshur County on the following day without incident. After remaining there until the morning of June 28, Colonel Heck returned with his command to their camp on Rich Mountain. The purpose of the occupation of Buckhannon is not known.”

Armstrong, Pg. 12

Actually, the purpose of Heck’s occupation is known, because Heck himself mentioned it in his post-parole report on his activities in the Northwest, published in The Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Series I, Vol. II.

“On June — I was ordered by General Garnett to take part of my regiment and all the wagons under my command and go to Buckhannon on a foraging expedition, a report of which you have. The day after we left Buckhannon, June –, the enemy, under General Rosecrans, about 5,000 strong, occupied the place and was very soon largely re-enforced.”

O.R., Pg. 255

Unfortunately, the report Heck mentions does not appear in the Official Records, but it does appear elsewhere. At least two letters from Heck made their way into the Staunton Spectator and Richmond Daily Dispatch, both on July 9. 1861.

According to Heck, he left camp on June 26th with 20 wagons and 300 men, including the Churchville Cavalry commanded by Capt. Franklin F. Sterrett. The cavalry rode out ahead, and as they approached a mill on the outskirts of town, they were fired on by 25 men concealed in ambush in a thick wood. Heck named the Union commander as Col. Henry F. Westfall. This confirms key details from William Cutright’s story in History of Upshur County. Cutright also named Henry F. Westfall as the Union Home Guard commander and stated that the skirmish happened “at the Ridgeway grist mill.”

Another key element Heck confirmed was the taking of two prisoners: Arthur G. Kiddy and James L. Jennings. Cutright wrote that the men were captured on the Clarksburg and Buckhannon turnpike and taken to Staunton in chains. Although Heck doesn’t name them, he did write “We arrested two men.”

So who was the “Col. Turk” that Cutright spoke of? He may have been referring to Rudolph Turk (1817-1890), sheriff of Augusta County, Virginia, and a militia colonel before the war. In May 1861, Turk helped organize volunteer companies in Staunton, then went to Philippi to assist Porterfield as an ordinance officer. In his post-parole report, Heck mentions “On the 25th [of May] Colonel Porterfield received a re-enforcement of six or seven raw recruits, infantry and cavalry, under Col. R. Turk.”

Turk was subsequently made a captain in the Confederate Army and reported to Staunton to work as a quartermaster overseeing wagons, artillery caissons, and ambulances.

It’s possible Rudolph Turk accompanied Lt. Col. Heck on his trip from Staunton to Rich Mountain. As a quartermaster, Turk could have supervised the acquisition of supplies at Buckhannon and accompanied the wagon train back to Beverly, where the captured provisions would be doled out in the coming weeks. Unfortunately, Heck never mentioned Turk in any of his reports.

Half-remembered stories from aging Civil War veterans aren’t the most reliable sources, but it would be quite a coincidence if Capt. Turk wasn’t involved with the expedition. I found an article in the Cleveland Morning Leader that gave an exaggerated account of the Confederate withdrawal from Buckhannon, stating that 30-40 rebels were killed, including “their Captain (named Turk)”.

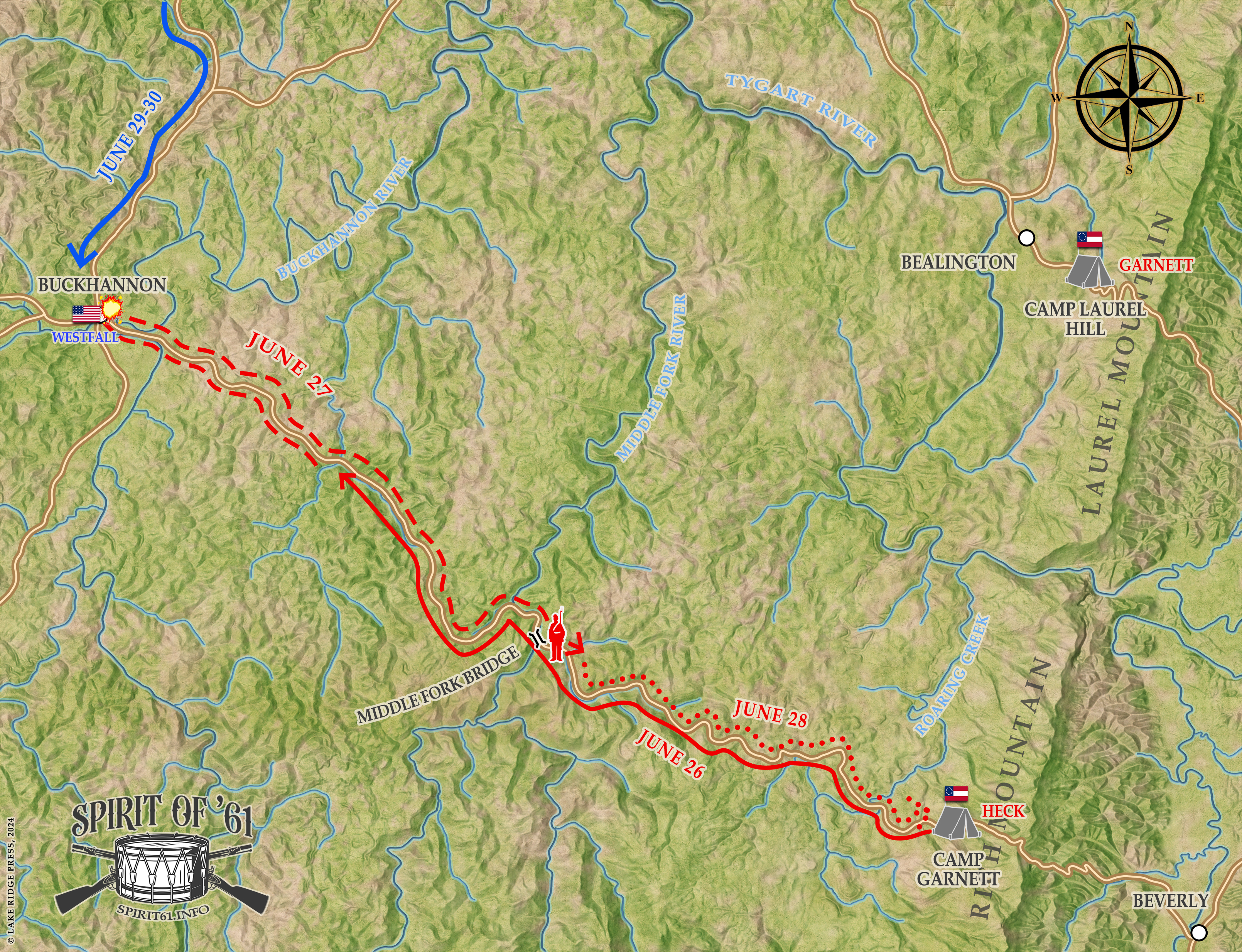

The map below depicts the route of Heck’s expedition. They left Camp Garnett on June 26, 1861, marched 18 miles, and camped five miles from Buckhannon. The following day, they entered Buckhannon and procured supplies, then marched back to the east bank of the Middle Fork River, where they had a picket post guarding the bridge. On June 28, they returned to camp.

Though a minor event in the grand scheme of things, especially where the Civil War is concerned, determining exactly what happened on Heck’s expedition to Buckhannon fills in a gap in our knowledge of the Tygart Valley/Rich Mountain Campaign. It helps us better understand the supply issues Confederates faced, and the role of Unionist home guard units in Northwestern Virginia in 1861.

Sources

Armstrong, Richard L. 25th Virginia Infantry and 9th Battalion Virginia Infantry. Lynchburg: H.E. Howard, Inc., 1990.

Cutright, William Bernard. The History of Upshur County, West Virginia: From its Earliest Exploration and Settlement to the Present Time. Buckhannon: By the author, 1907.

Haselberger, Fritz. Yanks from the South! The First Land Campaign of the Civil War. Baltimore: Past Glories, 1987.

Hotchkiss, Jedediah. “Virginia” in Confederate Military History, Vol. 3, edited by Clement A. Evans. Atlanta: Confederate Publishing Company, 1899.

The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Series I, Vol. II. With additions and corrections. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1902.

Daily Dispatch (Richmond) 9 July 1861.

Morning Leader (Cleveland) 12 July 1861.

Staunton Spectator (Staunton) 9 July 1861.

One thought on “What the Heck? Decoding Lt. Col. Jonathan M. Heck’s Expedition to Buckhannon in June 1861”