When a brief Civil War skirmish near Alexandria left two men dead, its aftermath sparked outrage on both sides. A Virginia woman’s diary captured the moment in gut-wrenching detail.

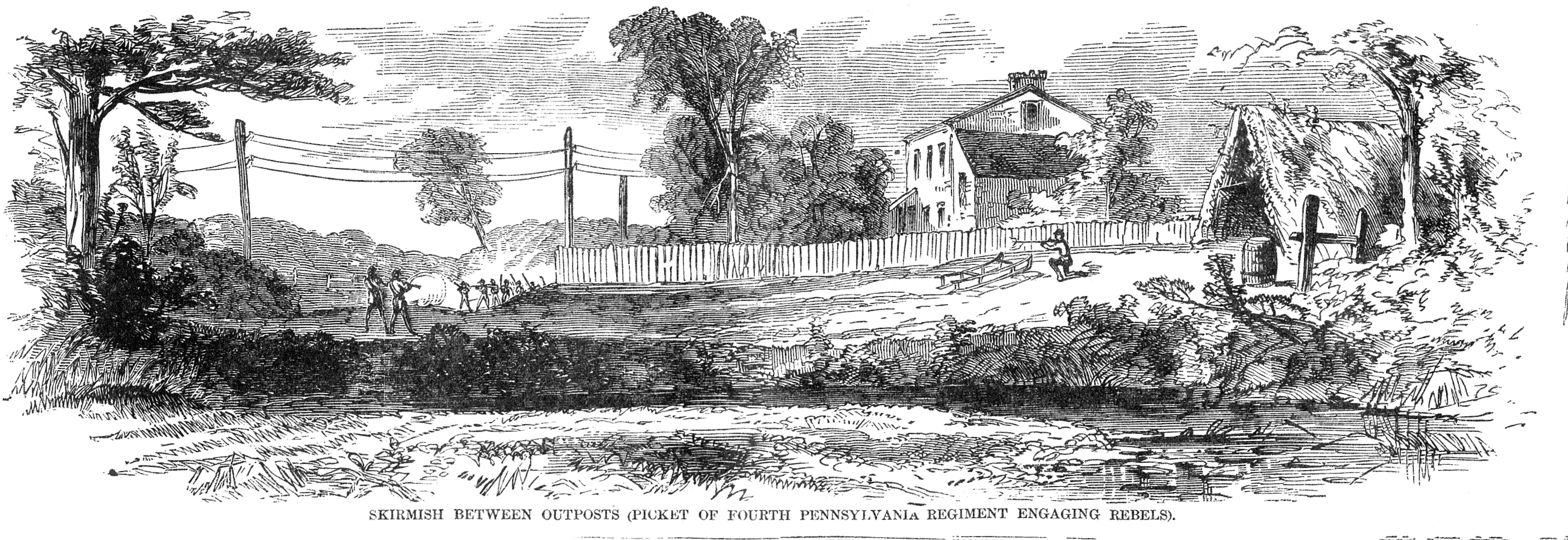

Before sunrise on the morning of Sunday, June 30, 1861, a brief but deadly clash unfolded just southwest of Alexandria, Virginia, where Confederate scouts encountered Union pickets at the intersection of Old Fairfax and Telegraph roads. The engagement, though small in scale, left two men dead—one Union, one Confederate. What might have passed into obscurity as a mere footnote of the war lives on vividly through the eyes of Anne Frobel.

Sisters Anne S. Frobel, 45, and Elizabeth D. Frobel, 43, lived on a 114-acre farm inherited from their mother called “Wilton Hill” about 2.5 miles southwest of Alexandria. When the Union Army crossed the Potomac River and invaded northeastern Virginia on May 24, 1861, Anne decided to record a diary of events as she and those around her experienced them. She was conscious that history was being made at her doorstep.

Wilton Hill was located between Old Fairfax Road and Telegraph Road, just west of where the two came together. Telegraph Road continued north, crossed Cameron Run, and joined the Little River Turnpike in front of Shuter Hill, just west of Alexandria. Anne was, if not an overt secessionist, sympathetic to the cause. She had no shortage of disparaging remarks for the Union soldiers occupying that section of Virginia, especially when they stole her livestock. Her detailed narrative is a treasure trove for anyone interested in the war’s impact on civilians in northern Virginia.

The Frobel sisters owned several slaves. Among them was a man named Charles who served primarily as their coachman. Charles was in Alexandria on business when the small expedition of Alabama and Virginia troops scouted the southern approaches to Shuter’s Hill and Alexandria. At the intersection of Old Fairfax and Telegraph roads, they ran into pickets from the 4th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry (3 Months) and a deadly firefight ensued.

On Monday, July 1, as Charles was returning to Wilton Hill, he encountered a party of Union soldiers carrying the body of the deceased Confederate across the bridge over Cameron Run. Anne Frobel related the following story in her diary:

“Monday morning, Charles came home this morning with great news and in much excitement. A party of rebels came down last night and fired into the pickets at South run. There was a good deal of noise making and yelling and bullets whistling through the woods in every direction one Confederate was killed and two yankees. As he, Charles, came from town a little after sunrise he found the roads filled with noisy soldiers.

“The whole face of the earth seemed to be alive with them. The Confederates had all retired. When he got near Cameron run he met hundreds of yankees they had the dead body of a man on a plank carrying him toward town with his legs and arms swinging, and every few steps they would fling him on the ground and kick and knock and beat him with their guns until it was sickening to look at- and such a noise, such hooping and yelling! and O-O-such curses and blasphemy we never did hear. When they met him they dashed the dead man right down before him—just at his very feet and screamed and yelled at him to know if he did not want to see a dead rebel. Charles seemed to be sick and disgusted with their beastly doings said he thought they may be satisfied when they have taken the man’s life he was dead and that was enough. After breakfast we went out to reconnoiter the premices and returned with the information, “dat dem rebels as dese people call em” had passed through this place last night and for fear of being impeded in their retreat had opened all our gates and fences, but he did not think they returned the way they went as he couldn’t find any of their returning foot marks.

“We did not go to town for several days after the attack on the pickets and when we reached the place where the skirmish took place Charles pointed it out to us “des is one place, and dat is tother, where the soldiers wuz killed, de rebel wuz foun over yander hang in ove de fence, da kil him gis is he wuz climbin over de fence. It was dreadful to see two immense stains of blood, but it was newly obliterated by travel we could only see the outlines. In town we heard the whole story pretty much as we had heard it before. Jolly was the name of the poor Southern soldier, from Georgia—after treating his body in such a savage indecent manner on the road, they got it into town, doubled it up and put it in a goods box, placed it in a wheelbarrow and carried it out to Penny Hill the pauper burying ground, scratched a hole and tumbled him in. The whole town was up in arms about such unheard of indecent doings and some of the gentlemen of the town called on the Provost Marshal and said to him they had come to ask Christian burial for a Soldier—The request seemed to be quite a startling one, but after some deliberation it was acceded to, of course they could not do otherwise. These gentlemen went straight to the undertaker and ordered what they wanted. They had the body taken up and prepared in the nicest—neatest manner, he was dressed in the very best and nicest of clothes that could be purchased, and everybody seemed to think it a privilege and honor to contribute, some one article and some another, the very best and handsomest casket the town could afford was procured—all the carriages in the town—all the ladies turned out—every body men, women and children—white and black attended poor Jolly’s remains to his grave. The streets were filled with yankee soldiers looking on, and one of them said he didn’t believe if Lincoln had died he could have such a funeral. Some one answered, “no not in Alexandria he could’ ent” Poor Jolly! his was the largest funeral ever seen in Alex[andria] and his first blood spilt in this part of the country in the Southern Cause.”

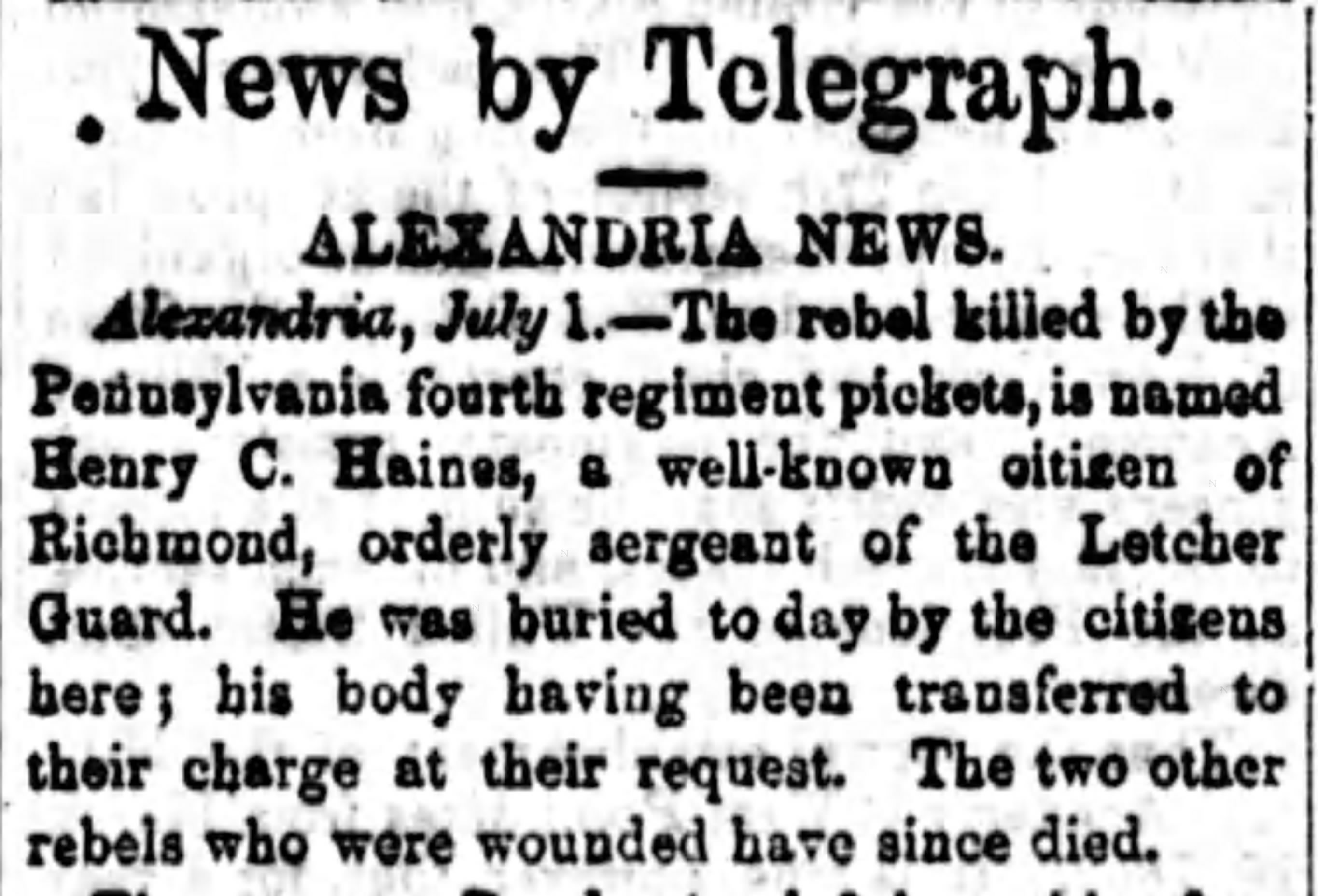

Anne and Charles’ account includes vivid details but also several inaccuracies. The deceased Confederate was not a Georgian named “Jolly,” but a Virginian from Richmond named Henry C. Hanes, a sergeant in the Governor’s Mounted Guard cavalry company. Although he was among the first Confederates killed in Fairfax County during the Civil War, he was not the very first. It is also unclear what specific “part of the country” Anne was referring to in her remarks.

Only one Union soldier was killed: Pvt. Thomas Murray. Another man, Llewelyn Rhumer, was wounded.

The following notice in the National Republican, a Washington, D.C. newspaper dated July 2, 1861, confirms several details from Anne’s diary, including that Alexandria residents requested custody of Hanes’s body and held a funeral for him before burying him in town.

The story of the aftermath of the Action at Pike’s Creek and the fate of Sergeant Henry C. Hanes’ remains, as recounted in Anne Frobel’s diary, illustrates how quickly wartime chaos can blur facts—and how personal narratives, even when inaccurate, preserve emotional truths.

The brief clash near Alexandria, the indignity of Hanes’ initial burial, and the town’s effort to correct that wrong reflect the tangled loyalties and moral tensions civilians faced under occupation. Through Anne’s perspective and Charles’s testimony, we see not only the violence of war but also a community’s attempt to uphold dignity amid it. Her diary, though flawed, remains a vital record of how ordinary people experienced and made sense of extraordinary events.

Sources

Frobel, Anne S. The Civil War Diary of Anne S. Frobel of Wilton Hill in Virginia. McLean, VA: EPM Publications, Inc., 1992.

Harper’s Weekly (New York, NY) 20 July 1861.

National Republican (Washington, DC) 2 July 1861.

Wenzel, Edward T. Chronology of the Civil War in Fairfax County, Part I. CreateSpace: By the Author, 2015.