Once an obscure Civil War outpost, the importance of Cloud’s Mill has resurfaced through original research, offering a rare glimpse into Northern Virginia’s lost wartime landscape.

Earlier this year, we completely revised our entry on the Skirmish at Arlington Mills after original research revealed the action actually took place three miles south, at Cloud’s Mill. But where was Cloud’s Mill—and more than 160 years later, does anything of it remain?

Today, Northern Virginia would be unrecognizable to the men who fought there during the Civil War. Suburban sprawl has reshaped the landscape. What the war didn’t destroy, modern development has erased, and little effort has been made to preserve historical landmarks and structures.

Cloud’s Mill, as it came to be known, was built between 1813 and 1816 just north of the Little River Turnpike (now Duke Street). Mordecai Miller was one of its early owners, and at various times it was called Triadelphia Mill. James Cloud owned it from 1835 to 1863. I haven’t been able to determine exactly when the mill was demolished, but a February 25, 1961, letter in the Richmond Times-Dispatch said it was likely torn down in the late 1930s or early 1940s.

In the 1970s, Alexandria Archaeology discovered remnants of the mill race near a townhouse development. The real estate developer took an interest in preserving what remained. On May 9, 1987, Costain Washington Inc., the Holmes Run Committee, and the Alexandria Archaeological Commission dedicated a memorial marking the site of the surviving section of the mill race.

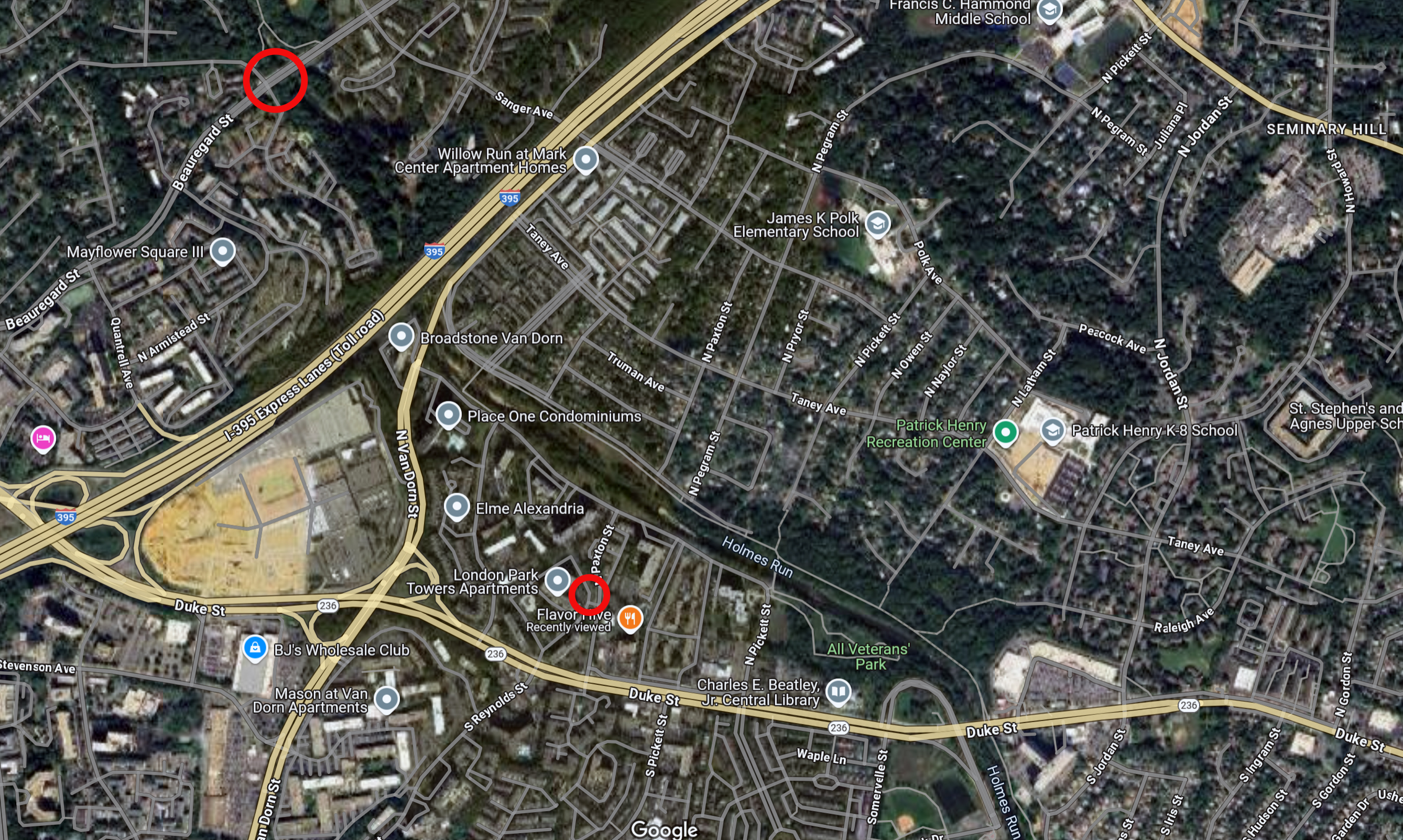

In the following modern Google Earth satellite image, the location of the Cloud’s Mill Race marker on North Paxton Street is circled in red, as is the intersection of Beauregard and Morgan Streets, where the text explains that the mill race diverted water from Holmes Run to turn the mill wheel.

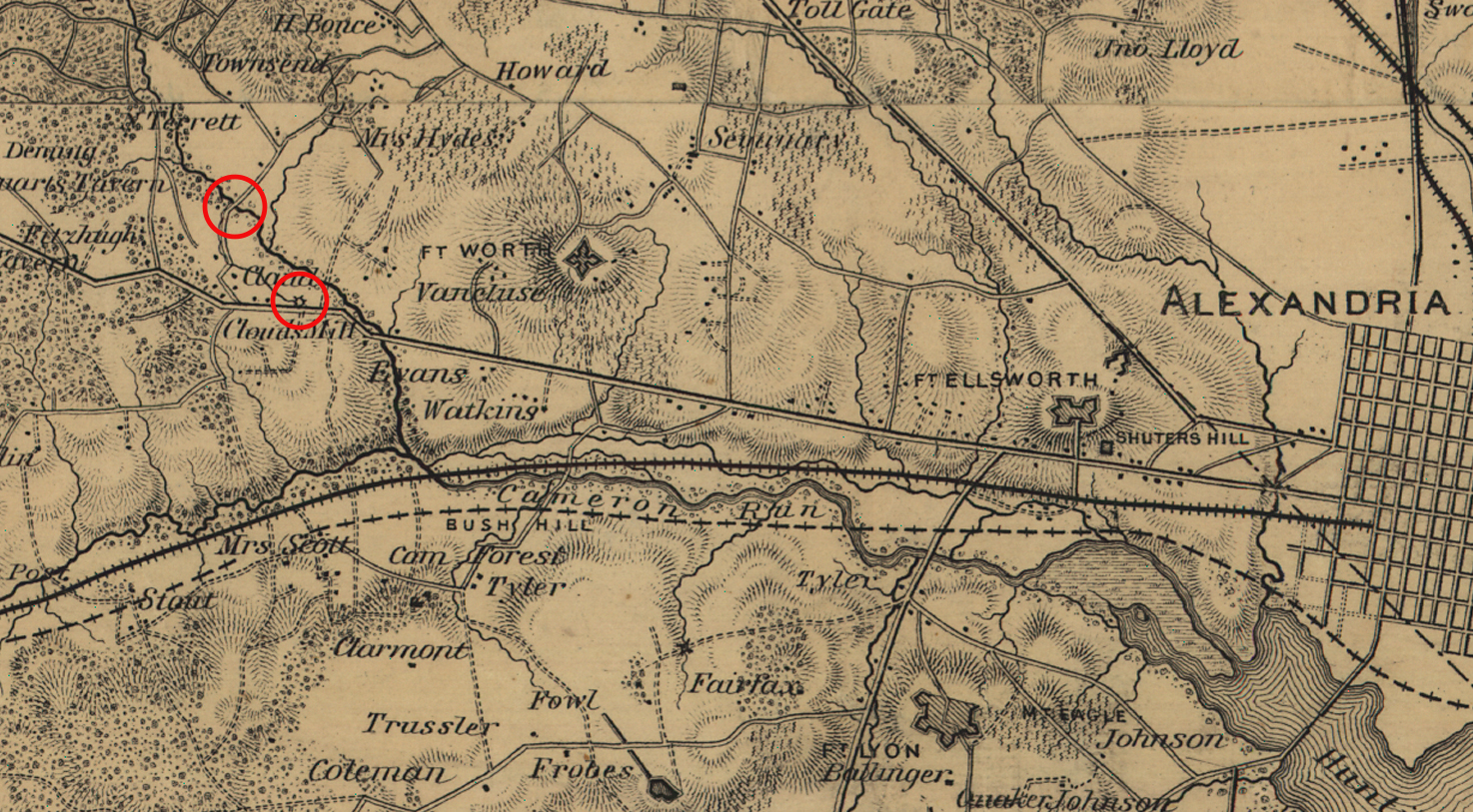

Below, you can see the same locations in an 1862 map of northeastern Virginia, courtesy of the Library of Congress Geography and Map Division. It’s faint, but you can see the mill race coming down just north of the road, which it follows for several yards before turning east toward the mill.

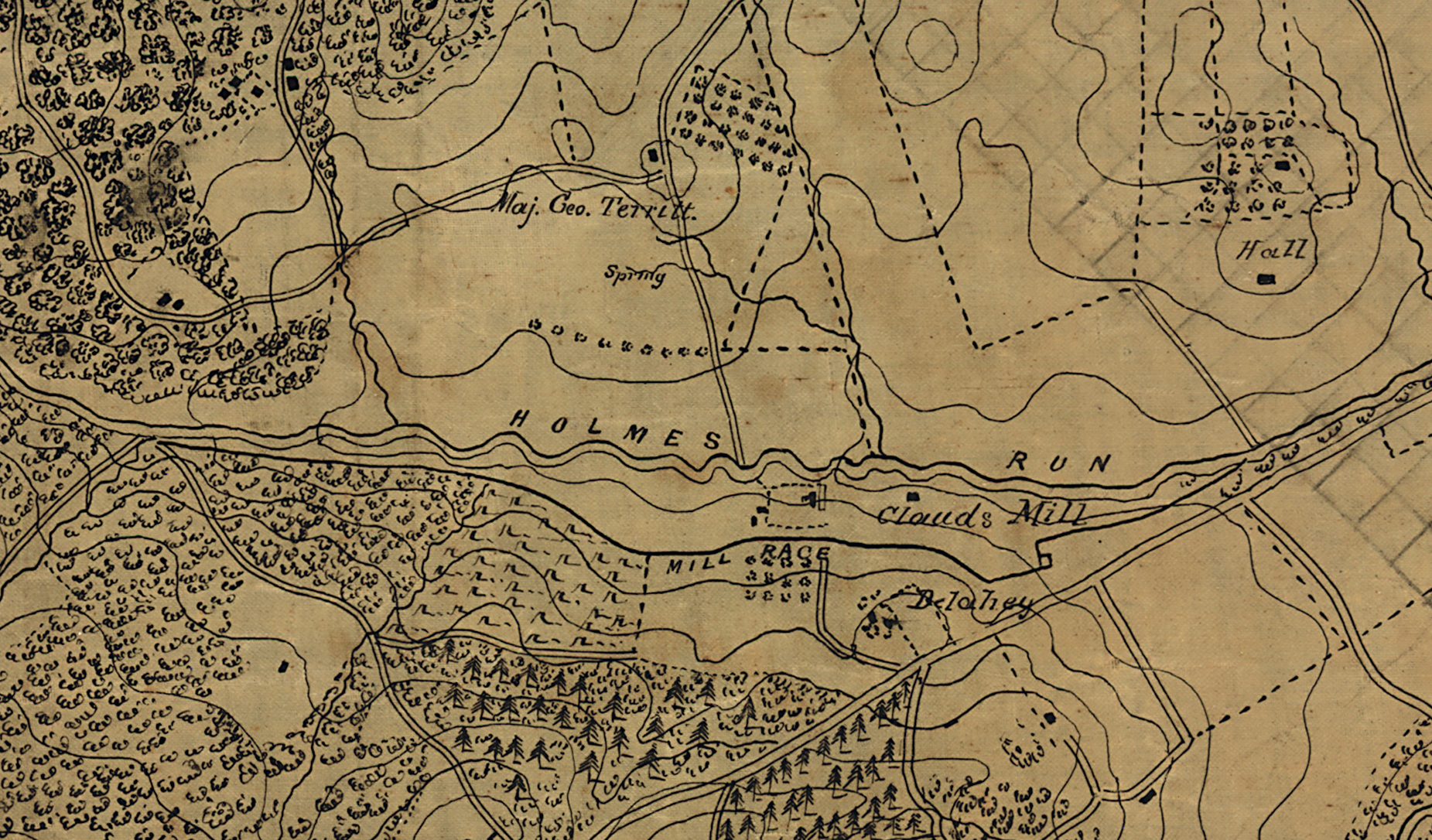

The undated Civil War-era map below shows Cloud’s Mill and its mill race in much more detail, although the exact contours of Holmes Run and the road appear loosely sketched and not entirely accurate. Cloud’s Mill was described as being located near the road, whereas on this map it is next to Holmes Run, not even along the mill race.

What did the mill look like? In a lengthy letter published in the New York Leader on July 6, 1861, under the pseudonym Harry Lorrequer, Private Arthur O’Neil Alcock, Company A of the 11th New York, wrote:

“Cloud’s Mill, of which you have heard so much, though it has become quite an institution with us as an outpost, has nothing about it that is in the least degree picturesque, or, indeed, remarkable in any way. It is a plain four-story brick building, standing a little back from the road to Fairfax, and bears the name of its owner, who resides about a quarter of a mile further on, on the same side of the road. Companies B, I, and K, have alternately been stationed at the Mill, and Company A is now there. On several occasions we have visited the different companies there, and are indebted to Captains Byrne, Wildey, Purtell, and Coyle for hospitalities, and although we have been some good times the least resemblance to certain old ivy-covered structures situated on hill sides, where the busy wheel is turned on its axis by a babbling brook, whose sparkling water is dashed into shining atoms over the jagged rocks that line its steep inclining bed, and whose swift moving surface is ever and anon broken by the leaping trout. Oh! No. Cloud’s Mill is not the Mill par excellence of romance—so treasured in the minds of the novel readers—but as we have said, a most ordinary common place brick building, noted for nothing but the millions of horrible fleas bred in its vicinity, the scantiness of the muddy fluid that stagnates in the so-called, or rather mis-called mill stream, that winds its sluggish way through a much neglected meadow, and almost hidden beneath a wild growth of weeds and brushwood. Indeed, were it not for the recollection of the hot biscuits furnished to the Captain’s table by the hands of the charming “Ida,” we doubt very much that we should have soiled so much good paper by writing of Cloud’s Mill at all. As a strategic point, it amounts to nothing—commands nothing—not even respect—as an outpost, it is but an apology for a guard-house—and, so much for the Mill, that possesses not even a maid to attach to it a coloring of romance or sentiment.”

Alcock described Cloud’s Mill as plain and unremarkable—a four-story brick building set back from the road. The mill race was overgrown, and the entire property appeared poorly maintained.

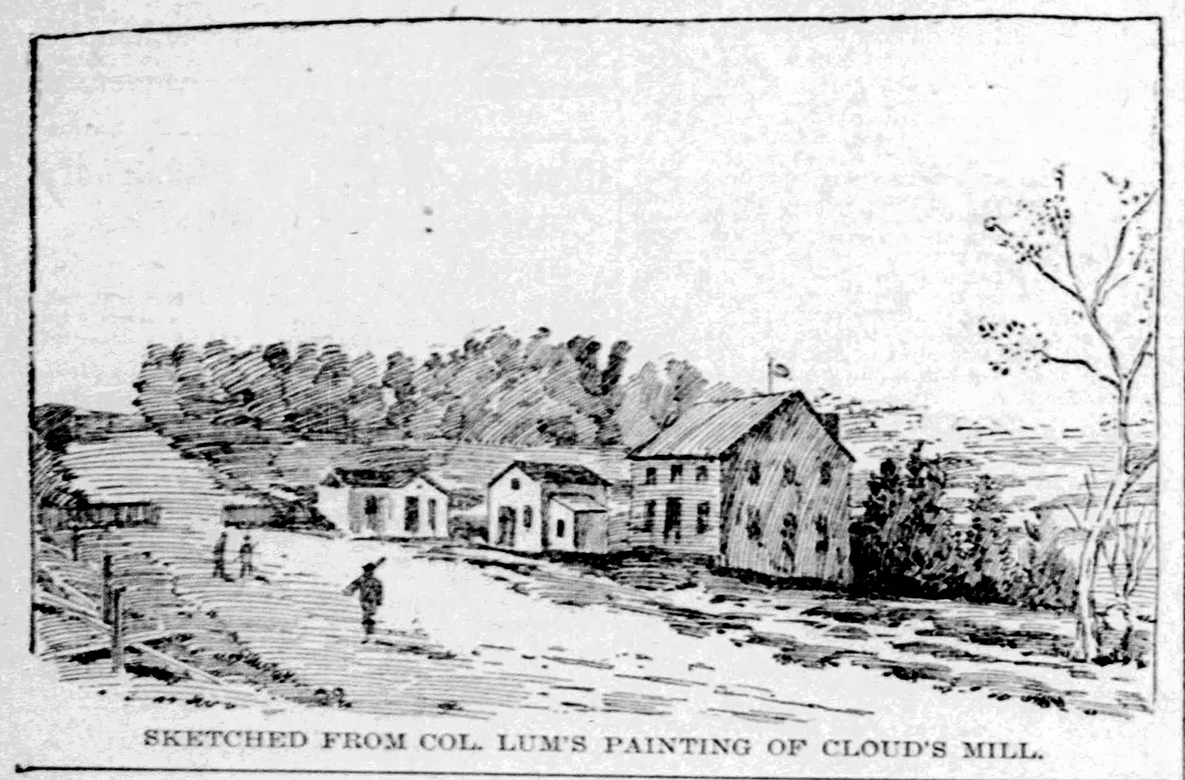

After the war, veterans of the 1st Michigan Infantry Regiment remembered their nights at the mill more fondly than their New York comrades did. Charles F. Lum, formerly of the “Detroit Light Guard,” even painted a scene of the mill for an 1896 reunion. The sketch below, based on his painting, later appeared in a newspaper:

In the sketch, you can see the mill is the most prominent building just right of center. There are two more buildings, one of which was a barn. There are barricades across the road and several soldiers patrolling.

Phoenix Mill (also known as Dominion Mill), located near 3640 Wheeler Avenue and built in 1801, is one of Alexandria’s oldest surviving mills and may be the only one still standing that predates the Civil War. It features a curved, rather than triangular, gabled roof. As a surviving brick mill from the early nineteenth century, it’s the closest thing you can see today to what Cloud’s Mill would have looked like.

The Civil War-era photograph below, taken by Mathew Brady, shows what Phoenix Mill looked like in the 1860s. This photo has sometimes been misidentified as Cloud’s Mill, suggesting the two may have looked very similar.

Today, little remains of Cloud’s Mill beyond a faint trace of its mill race and a small memorial marking the site. Though the mill itself has vanished, historical records, wartime accounts, and surviving structures like Phoenix Mill offer a glimpse into what it once was. Once a modest, unremarkable outpost during the Civil War, Cloud’s Mill has gained new significance through its link to one of the first deadly incidents of the war in Virginia—one that, despite the passage of time and sweeping development, hasn’t been entirely forgotten.

Sources

Beiro, Jean A. A History of Cloud’s Mill in Alexandria, Virginia. Edited by John G. Motheral. Alexandria: Alexandria Archaeology Publications, 1986.

The Detroit Free Press (Detroit, MI) 25 February 1896.

Richmond Times-Dispatch (Richmond, VA) 25 February 1961.

Schroeder, Patrick A. and Brian C. Pohanka, eds. With the 11th New York Fire Zouaves in Camp, Battle, and Prison: The Narrative of Private Arthur O’Neil Alcock in the New York Atlas and Leader. Lynchburg: Schroeder Publications, 2011.