In 1861, control of the Potomac River was critical to both Union and Confederate strategies, as it formed a key geographic boundary. While the Union secured the upper river and gained a foothold in northeastern Virginia, Confederate coordination between the Shenandoah and Manassas Junction led to victory at Bull Run and enabled a temporary blockade of the U.S. capital by that autumn.

The Potomac River, a 405-mile waterway originating in the Potomac Highlands of what was then northwestern Virginia and terminating in the Chesapeake Bay, formed the antebellum boundary between Virginia and Maryland. Virginia’s secession would have transformed this boundary into an international border, placing the U.S. capital on the opposing shore. Therefore, securing the Potomac was critical for Union war planners, both to facilitate the movement of friendly troops and supplies and to deny the enemy the same advantage. To enforce President Lincoln’s blockade and secure the river, the Union Navy formed a flotilla to patrol the Virginia shore and prevent Maryland sympathizers from supplying Confederates across the river.

While the Potomac River offered Virginia and the Confederacy a natural barrier against invasion, its length posed significant defensive challenges. Insufficient forces existed to effectively secure every crossing. Consequently, establishing interior lines to counter Union advances became a key element of Confederate strategy. Initial deployments focused on Harpers Ferry and Centreville, but these positions were subsequently abandoned as the strategic situation evolved. This effectively ceded control of the river to the Union, save for the sector east of Fredericksburg, where Confederate shore batteries hindered Union naval operations.

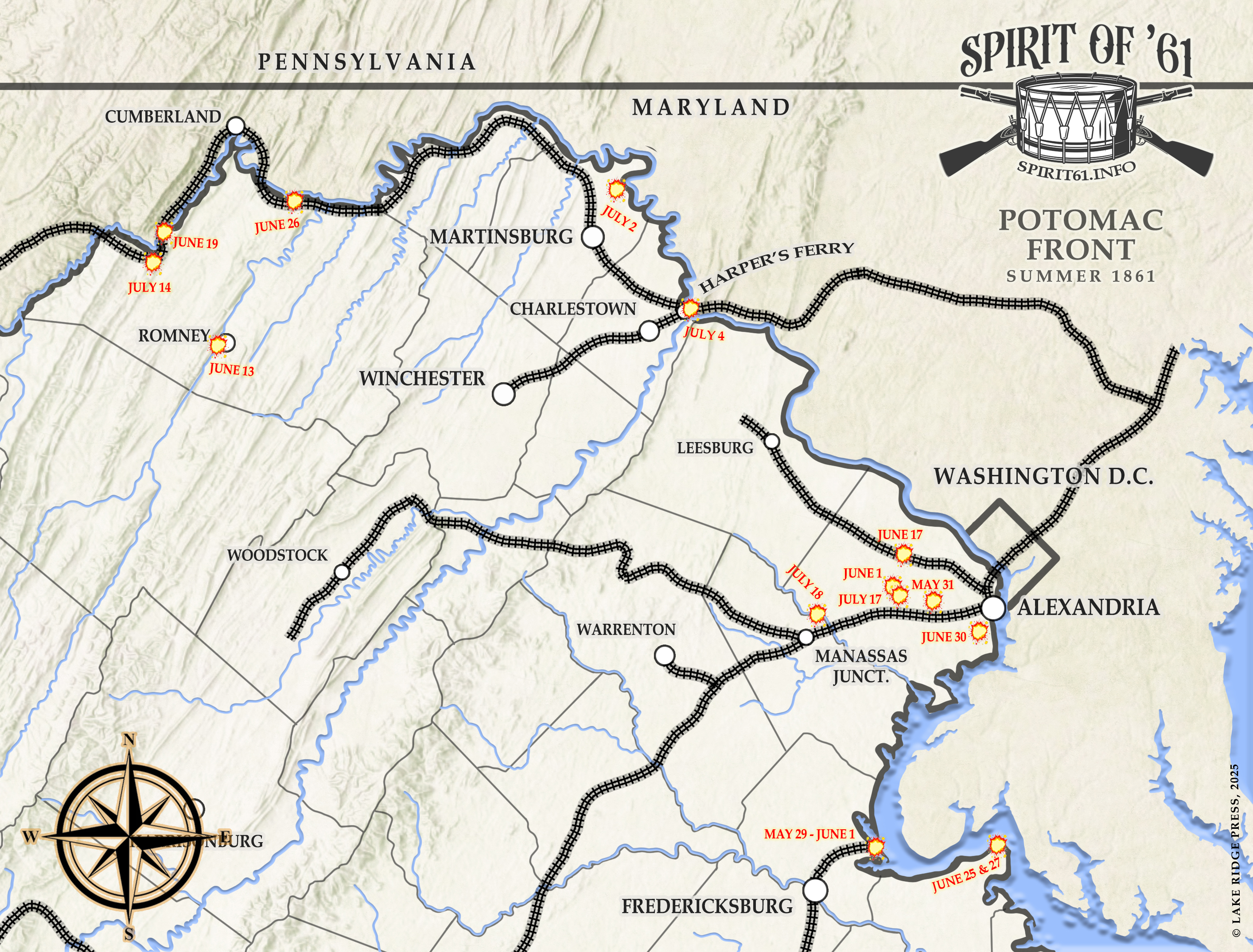

The Potomac Front can be subdivided into upper and lower, using the Shenandoah River as the dividing line. Each area was assigned separate military districts but had mutually-supporting objectives. The success or failure to coordinate forces between these two areas would decide the fate of the whole. The First Battle of Bull Run / Manassas was the culminating event of military activity on this front in the spring and summer of 1861. The Confederates successfully united their forces at Bull Run and won the battle. While the Union Army had numerical superiority, their failure to prevent Confederate coordination led to a disastrous loss.

Upper Potomac

Northwest of Great Falls, the Potomac River is not ideal for navigation. Constructed between 1828 and 1850, the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal was designed to facilitate the flow of river traffic between Washington, D.C. and Cumberland, Maryland. The Baltimore & Ohio Railroad served the same purpose on land. These were vital transportation routes linking the U.S. capital with the west. Harpers Ferry was a strategic point on this route, and home to a U.S. arsenal. No major battles were fought in this sector in the spring and summer of 1861, but there were several skirmishes, including the largest at Hoke’s Run / Falling Waters.

To oversee this subregion, the Union Army established the Department of Pennsylvania on April 27, 1861, headed by 69-year-old Major General Robert Patterson. The 11th Indiana Regiment, acting semi-independently, was stationed in Cumberland, Maryland. Initially, their strategy was to prevent Confederate incursions into Maryland and protect the B&O Railroad. Under pressure to act more aggressively, Patterson finally crossed the Potomac on July 2 with a mission to tie up Confederate Brigadier General Joseph E. Johnston’s army in the Shenandoah Valley. His failure contributed to the Union disaster at the Battle of Bull Run.

The Confederates in the Upper Potomac had similar but opposite objectives: delay Union forces and damage the B&O Railroad to sever that vital transportation route. Before Virginia officially joined the Confederacy, its militia assembled at Harpers Ferry under the command of Col. Thomas J. Jackson. Brig. Gen. Joseph E. Johnston took command on May 23rd and formed the Army of the Shenandoah. Johnston evacuated Harpers Ferry to Winchester, where he could more easily access the Manassas Gap Railroad and reinforce P.G.T. Beauregard at Manassas Junction, which he did on July 20-21. This successful maneuver tipped the scales at Bull Run, winning the battle for the Confederacy.

Lower Potomac

The Potomac River below Harpers Ferry was vital to defense of Washington, D.C. The national capital was in a precarious position, surrounded by Virginia and Maryland. Maryland, despite declaring neutrality, had a significant secessionist population. The Potomac was a critical lifeline, carrying supplies, troops, and military orders between the capital and Chesapeake Bay. Securing the lower Potomac was a top priority for both President Abraham Lincoln and General Winfield Scott. In mid-May, U.S. Navy Commander James Harmon Ward organized a small “flying squadron,” later known as the Potomac Flotilla, to enforce a naval blockade and control access to the river.

To organize the District’s defense on land, the Union Army created the Military Department of Washington led by Brigadier General Joseph K. Mansfield. Mansfield advocated an aggressive defense by establishing a bridgehead on the southern side of the Potomac River. The town of Alexandria, Virginia and its deep water port were seized on May 24, 1861, as was Arlington Heights and other strategic terrain in that corner of northeastern Virginia. On May 27th, Brigadier General Irvin McDowell was appointed to command the new Department of Northeastern Virginia.

Virginia’s provisional army divided this subregion into two sectors: the “Alexandria Line” and Military Department of Fredericksburg. Despite its name, Virginia’s high command did not intend to defend Alexandria or the area immediately to the south of Washington, D.C. Instead, its forces were concentrated at Centreville with outposts at Fairfax Court House and Alexandria. Alexandria was abandoned as soon as the Union Army crossed the river. The army’s headquarters moved south to Manassas Junction, using Bull Run as a natural defensive barrier. East of Fredericksburg, shore batteries at Aquia Landing and an aggressive defense of Mathias Point effectively prevented the Potomac Flotilla from accomplishing its mission.

A succession of commanders oversaw this strategic area. Colonel Philip St. George Cocke initially organized Virginia volunteers in northeastern Virginia and was largely responsible for formulating the strategy of using the Manassas Gap Railroad to coordinate mutual support with forces in the Shenandoah Valley. Brigadier General Milledge Luke Bonham superseded him on May 21st but was not in charge long before Brigadier General Pierre Gustave Toutant-Beauregard arrived to take command. By that time, the Confederate government had taken control of military operations in Virginia. Colonel Daniel Ruggles initially commanded the Department of Fredericksburg but he was replaced by Brigadier General Theophilus H. Holmes.

Despite ceding a foothold to the Union Army in northeastern Virginia, effective coordination between Confederate forces saved Beauregard’s army from defeat at the First Battle of Bull Run / Manassas. The Confederates would never regain control of Alexandria, but in the fall of 1861, they effectively sealed off the Potomac River using shore batteries, blockading Washington, D.C. The situation remained unchanged until the spring of 1862.

Sources

Avirett, James B. The Memoirs of General Turner Ashby and His Compeers. Baltimore: Selby & Dulany, 1867.

Connery, William S. Civil War Northern Virginia 1861. Charleston: The History Press, 2011.

Davis, William C. Battle at Bull Run: A History of the First Major Campaign of the Civil War. Mechanicsburg: Stackpole Books, 1977, 1995.

Detzer, David. Donnybrook: The Battle of Bull Run, 1861. Orlando: Harcourt, Inc., 2004.

Fry, James B. “McDowell’s Advance to Bull Run” in Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, Vol. I. New York: The Century Co., 1887.

Frye, Dennis E. Harpers Ferry Under Fire: A Border Town in the American Civil War. Virginia Beach: The Donning Company Publishers, 2012.

Gottfried, Bradley M. The Maps of First Bull Run: An Atlas of the First Bull Run (Manassas) Campaign, Including the Battle of Ball’s Bluff, June – October 1861. New York: Savas Beatie, 2009.

Longacre, Edward G. The Early Morning of War: Bull Run, 1861. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2014.

Wills, Mary Alice. The Confederate Blockade of Washington, D.C. 1861-1862. Parsons: McClain Printing Company, 1975.