The Chesapeake Bay, a defining feature of Virginia’s maritime border, stretches approximately 200 miles south from the mouth of the Susquehanna River in Maryland to Cape Henry and Cape Charles, Virginia. It is the largest estuary in the United States, providing an important avenue for domestic and international trade and commercial fishing. The 170-mile long Delmarva Peninsula defines its eastern shore. The peninsula’s 70-mile long “tail” forms the Eastern Shore of Virginia.

Along the Chesapeake’s western shore lies Tidewater Virginia, a region shaped by the Potomac, Rappahannock, York, and James Rivers. These rivers, which flow into the Chesapeake, create three distinct peninsulas: the Northern Neck, Middle Peninsula, and Virginia Peninsula. This area played a crucial role in Colonial Virginia, and by the start of the Civil War, it remained home to some of the state’s wealthiest and most influential families. Plantation agriculture dominated the economy, and the enslaved black population often outnumbered free white residents.

In 1861, the bustling Virginia cities of Portsmouth and Norfolk sheltered the Gosport Navy Yard, a vital U.S. Naval facility. Just north of these cities, the confluence of the James, Nansemond, and Elizabeth Rivers created the expansive natural harbor of Hampton Roads. Its entrance was flanked by Old Point Comfort at the tip of the Virginia Peninsula to the north, and Sewell’s Point to the south. Fort Monroe, a stone and brick bastion-style fort built between 1819 and 1844, stood on Old Point Comfort.

On April 17, 1861, the Virginia Secession Convention voted in favor of secession, subject to a popular referendum to be held on May 23. Federal property in Virginia was in the crosshairs, including the Gosport Navy Yard and Fort Monroe. Secessionists argued they should be seized at once without waiting for the results of the referendum. The following day, Virginia Governor John Letcher telegraphed Confederate President Jefferson Davis: “Our object is to now secure the navy-yard at Gosport…”

Federal authorities had good reason to be worried. Dozens of desertions by Virginian officers and men made defense of the Yard untenable. On the night of Saturday, April 20, Commodore Charles Stewart McCauley, its commander, ordered the ships in the harbor sunk to prevent their capture and attempted to blow up the Yard. Virginia militia saved most of the arms and its large dry dock, however, including approximately 1,085 cannon of various sizes and 250,000 pounds of powder.

After the fall of Fort Sumter in South Carolina, Fort Monroe became the last remaining federal stronghold in the South. Rather than invest the fort and force its surrender, as the Confederates had done at Fort Sumter, Virginia opted for a defense in depth. They used the seized artillery from Gosport Navy Yard to fortify points around Hampton Roads and along the York and James rivers. Robert E. Lee, as overall commander of Virginia’s militia, placed the flamboyant Colonel “Prince” John Bankhead Magruder in charge of defending the Virginia Peninsula. Benjamin Huger, a South Carolinian, took command of Confederate forces gathering around Norfolk.

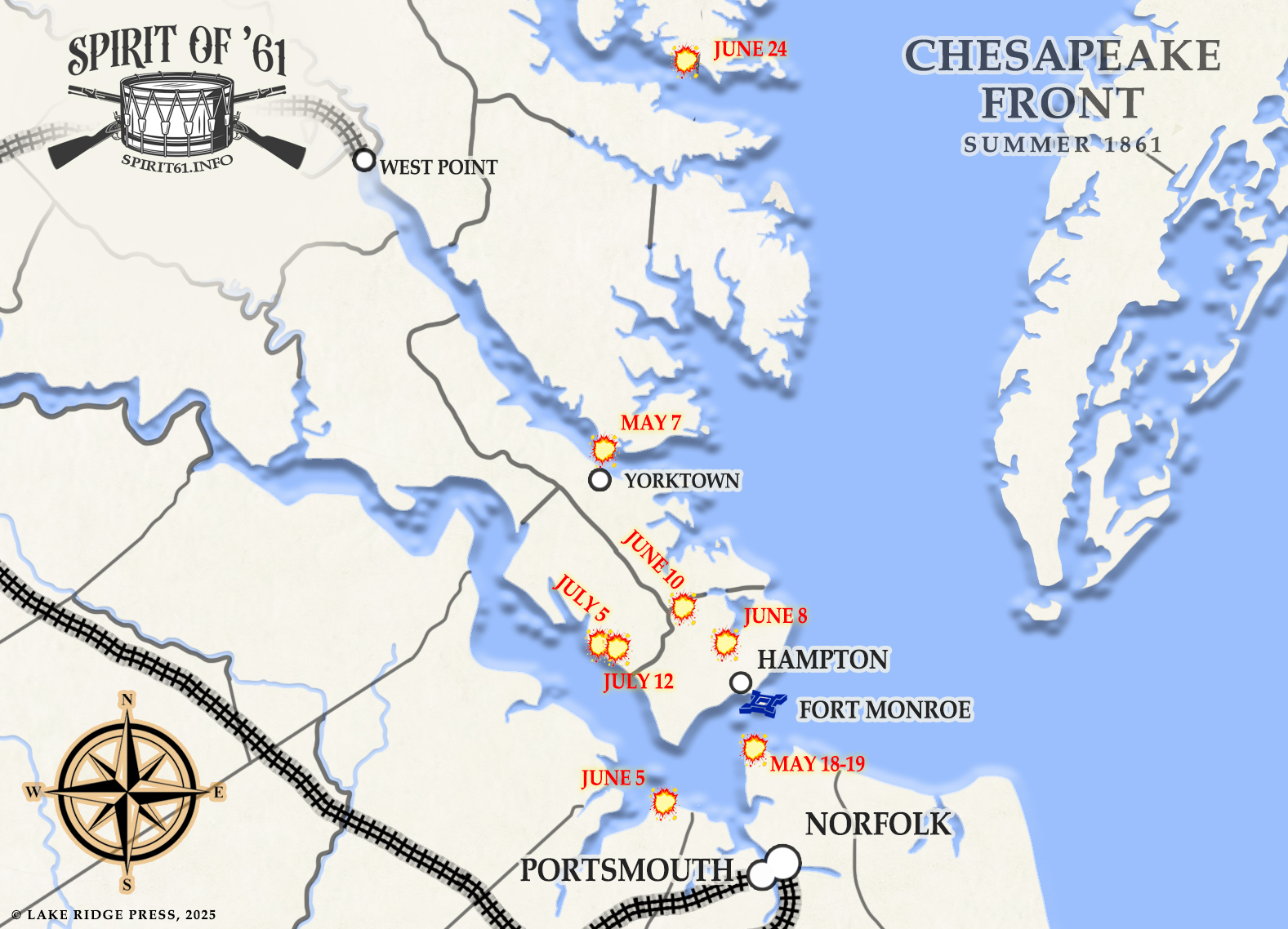

On April 27, President Abraham Lincoln extended his blockade of the seven original seceding states to include the ports of Virginia and North Carolina. The U.S. Navy formed the Atlantic Blockading Squadron, led by Flag Officer Silas H. Stringham, to enforce the blockade. On May 7, the first hostile exchange of fire in Virginia occurred between the converted steam tugboat USS Yankee and a shore battery at Gloucester Point, opposite of Yorktown on the York River. Neither side reported casualties.

On May 22, Brigadier General Benjamin F. Butler of Massachusetts assumed command of the Military Department of Virginia, which included everything within a 60-mile radius of Fort Monroe. Known for his aggressive leadership, Butler quickly sought to expand the Union’s foothold on the Virginia Peninsula. By the end of May, his forces had occupied the nearby towns of Hampton and Newport News. It was only a matter of time before Union and Confederate forces clashed.

This came on June 10, 1861 at Big Bethel Church. The resulting battle was an unambiguous Confederate victory, and, though small compared to what was to come, it involved over 6,000 combatants and resulted in 86 recorded casualties. After Big Bethel, only a few small skirmishes occurred on the Virginia Peninsula that summer, and major military operations in the area ceased until the following year.

The Confederate strategy in the Chesapeake in early 1861 was purely defensive, focusing on erecting fortifications and shore batteries to prevent Union forces from advancing up the Virginia Peninsula or York River. In this effort they succeeded, but the failure to seize Fort Monroe had lasting consequences for the remainder of the war. Norfolk would fall in early 1862, and Fort Monroe continued to be a staging ground for invasions of Virginia. Its sheltering of escaped slaves in 1861 impacted national policy, eventually leading to the Emancipation Proclamation.

One thought on “Map and Overview of the Chesapeake front”